Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

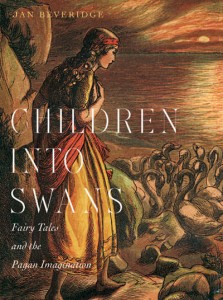

Jan Beveridge’s new release, Children into Swans: Fairy Tales and the Pagan Imagination, opens the door on some of the most extraordinary worlds ever portrayed in literature – worlds that are both starkly beautiful and full of horrors. In the spirit of this week’s festivities, the following excerpt looks at the Celtic roots of Hallowe’en, formerly known as Samain.

Jan Beveridge’s new release, Children into Swans: Fairy Tales and the Pagan Imagination, opens the door on some of the most extraordinary worlds ever portrayed in literature – worlds that are both starkly beautiful and full of horrors. In the spirit of this week’s festivities, the following excerpt looks at the Celtic roots of Hallowe’en, formerly known as Samain.

The eve of the first day of November, the Irish Samain, was the other central day in the Celtic calendar, marking the beginning of winter and also the Celtic New Year. The festival was another spirit night, but this haunted occasion was the dark opposite of Beltaine. From ancient times, all over Europe, the first of November was a festival to honour the dead. As early as the seventh century, the old pagan day had evolved in Christian tradition into All Souls Day, a day to offer prayers for the departed.

Something of the spirit of the old festival remains in the North American tradition of All Hallows’ Eve, or Hallowe’en, which was introduced to America in the 1840s with the immigrants who fled the Irish famine. Today’s carved pumpkins, ghosts and witches, costumed children trick-or- treating for candy are all remnants from the old Irish folk traditions and customs. On this eve of the first day of winter, the cattle had been brought home from the high pastures, the skies were cold, and the land was stark and grey. It was a night to either stay indoors or light a bonfire to ward off spirits. Traditionally on this night, warmcakes and cider were left on a table ready for any souls of the dead who would be visiting their old homes one more time. Sometimes, a turnip was hollowed out and a candle put in it to provide a beacon of light for these night visitors. A frightening face carved in it, like a jack-o’-lantern, would keep away the unwanted spirits abroad in the countryside. When gangs of mischievous boys, in masks and costumes impersonating the spirits that might be about, came to one home after another demanding pennies or sweets, they were seldom refused.

In Irish folklore, Samain was haunted by more than the dead – a whole host of spirits was on the move. Fairy mounds were open on Samain evening, and the old Sidhe, fairies, and ghosts rushed out of their hills. There are folk tales of a dance of the fairies led by the king of the dead and his queen, while other tales describe a fair held by the fairies with goods to sell: fresh berries, apples, and all kinds of fruit, shoes, bits of clothing, and jewelry. This looked just like a normal country fair, with crowds dressed in brightly coloured but old-fashioned clothing milling about and dancing. But it could only be viewed from afar; if one ventured close, it all disappeared.

(…)

Samain, or Hallowe’en, seems to have been a favourite motif of the ancient storytellers. Many of these stories are full of horrors, as the old stories often are, but I decided to conclude the chapter with this one, which I much prefer. This is a Celtic Samain story that is as beautiful as any we could imagine. It is also part of the Ulster Cycle. “Dream of Angus” (Aislinge Óenguso) portrays Samain, which issued in the pagan new year, as a pivotal day. The tale also presents the prevailing theme we have seen in the other stories – in the magical hours of Samain evening, it was possible for the visible and invisible worlds to come together. Angus was an Irish god of youth and love, and he was a son of the Dagda, high chieftain of the Tuatha Dé Danann. Both Angus and the Dagda are depicted from time to time as living in Brug na Bóinne, which has been identified as the prehistoric passage tomb, Newgrange, in County Meath. This is also the place to which Midir and Étaín flew in the shape of swans. It appears that this site, which was ancient when the Celts arrived in Ireland, caught the imagination of early storytellers both as a place where gods lived and as an entrance to the otherworld.

Dream of Angus

A maiden appeared to Angus one night, standing near the top of his bed like a vision in a dream. The next night she appeared again, this time with a harp, and played music for him. This was the princess Cáer Ibormeith. The girl was so radiant, and the dream vision so powerful, that the youth fell in love with her, but she never came to him again. Afterwards, he remained deeply haunted by her memory and became seriously ill. The king sent messengers throughout Ireland to find a girl like the one Angus had seen, and they searched for a whole year but to no avail.

Cáer was under an enchantment, in which for one year she was a human maiden and the next year she was a swan. Finally, on Samain evening, Cáer was found swimming on a lake with one hundred and forty-nine other swans, with silver chains between each pair. Angus stepped into the lake, and the moment he did he was transformed into a swan himself. The two swans, Angus and Cáer, swam towards each other and then flew into the air. They circled the lake three times singing glorious music. Then they flew away to the otherworld, the sidhe or mound of Brug na Bóinne, where Cáer remained with him forever.

To learn more about Children into Swans, or to order a copy online, click here.

For media requests, please contact Jacqui Davis.

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.