Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

TOMORROW: Making Toronto Modern Book Launch

6 – 8 pm at Swipe Design, Toronto

View Map ›

Join us tomorrow evening for the launch of Christopher Armstrong’s Making Toronto Modern at Swipe Design in Toronto.

Making Toronto Modern constructs Toronto’s architectural past to create a compelling narrative of how new ideas about modernism were debated, received, and embodied in new buildings. The following is an excerpt from the book.

The claim has often been made that avant-garde architects in Canada “evinced little interest in the more doctrinaire aspects of Modernism and certainly none of the interest in social reform that characterized European Modernism,” but this does not appear to be correct. One strand of Modernism, typified by the designs of Mies van der Rohe, did eschew a social mission. Instead he produced buildings that became an archetype for commercial towers, acceptable to business leaders in Toronto because they seemed practical and made their city appear increasingly like New York or Chicago. This impression was reinforced by Mies’s vast Toronto-Dominion Centre complex, which stood right in the heart of the city’s downtown, and by the fact that other designers followed in his footsteps in continuing to turn out office buildings that were pale imitations of the master’s model into the twenty-first century.

Yet the fact remains that from the 1960s onward some architects continued to debate how Modern designs might promote social amelioration. These discussions revolved around the need to change the look and the layout of the housing in which the vast majority of Canadians resided. The guiding assumption was that changing the built environment would offer a means to the improvement of society. In the 1940s the promoters of slum clearance in Toronto had been firmly convinced that new housing would improve lives, and that conviction survived during the second half of the century.

As the city grew rapidly many architects became persuaded that suburban developments filled with near-identical single-family homes on large lots were not only costly and ugly but produced undesirable social impacts. This conviction was particularly evident in discussions about the construction of new large-scale housing projects during the 1950s and 1960s. The hope was that careful planning of a variety of housing types, including row housing and apartment blocks laid out with due attention to the provision of community facilities, could create a more satisfactory milieu, especially for lower-income families.

(…)

Despite the growing demand for apartment living by the mid-1950s, high-rise towers continued to encounter strong criticism. Social work professor Albert Rose pointed out that before 1958 apartments had never exceeded 30 percent of total dwelling starts in Canada’s urban centres, but in that year reached over 36 percent and by the mid-1960s were running at nearly 55 percent. Metro Toronto had reached 50 percent in 1958 and soon expanded to over 60 percent. Still it was widely believed that high-rise buildings were a poor environment for raising children, though research on that point did not sustain such claims.

The editors of Canadian Architect followed Rose’s article with an analysis of the reasons why so many near-identical apartment blocks of dubious architectural merit were now being built. By the 1960s construction techniques for residential high-rises framed in reinforced concrete had become fairly standardized. Slab towers with about twenty storeys on top of a couple of underground parking levels could be constructed with reinforced eight-inch concrete one-way floor plates and stiffened by vertical shear walls to resist lateral wind forces located at approximately twenty-foot intervals, which also acted as convenient partitions. The speed and economy of such construction methods was increased by the development of flying forms, which permitted cranes to slip them out from a hardened slab and raise them up two storeys for reuse. The most common footprint was the doubleloaded slab, but the same methods could be used for smaller point towers and Y-shapes or cruciforms that drastically reduced construction costs but permitted relatively high densities on smaller lots.

The marxisant radicals who oversaw the creation of a tower for the residential Rochdale College on the northern edge of the University of Toronto campus at Bloor and St George Streets claimed to provide new models of social and intellectual life. Various modes of communitarian living were offered that would provide radical alternative lifestyles to the morays of modern capitalism. When the experiment was terminated in disarray, however, the building’s conversion into residences for the elderly did not prove too great a challenge. The structural forms reflected the grid that rose from the underground parking garage, which made the building much like its despised counterparts elsewhere.

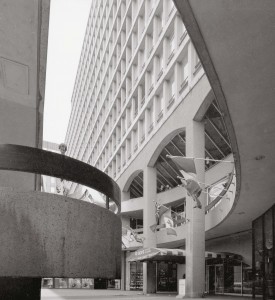

A more interesting variation on the format was devised by architect Gerald Robinson. The Colonnade development on Bloor Street just east of Avenue Road, completed in 1964, provided fifteen retail stores on the ground floor with fifty small boutiques above. This level, which aimed to create the impression of an indoor street, was reached by a striking staircase spiralling one and one-half turns from the street with no central support. Above were 160 apartments. The building also contained a 350-space parking garage as well as office and studio space, a theatre in the round, and even a farmers’ market. The framework was of reinforced concrete linked by small exterior columns to allow flexible room layouts.

High-rise apartment construction took off not only in the city proper but in the suburbs. The creation of Metropolitan Toronto permitted the speedy development of an expressway box (composed of Highways 401 and 427, the Gardiner Expressway, and the Don Valley Parkway) that, along with a program of arterial road construction, greatly facilitated automobile commuting. The development industry was quick to locate apartment complexes along these routes even at the outer edges of the built-up area. In contemporary photographs the cluster of towers located at the intersection of Bathurst Street and Steeles Avenue at the very edge of Metro appear striking on account of the open fields stretching beyond them to the north.

High-rise apartment construction took off not only in the city proper but in the suburbs. The creation of Metropolitan Toronto permitted the speedy development of an expressway box (composed of Highways 401 and 427, the Gardiner Expressway, and the Don Valley Parkway) that, along with a program of arterial road construction, greatly facilitated automobile commuting. The development industry was quick to locate apartment complexes along these routes even at the outer edges of the built-up area. In contemporary photographs the cluster of towers located at the intersection of Bathurst Street and Steeles Avenue at the very edge of Metro appear striking on account of the open fields stretching beyond them to the north.

Such developments had clear connections to longstanding ideas of the Modern movement in architecture. Tall towers set in parkland crisscrossed by broad roads harked back to Le Corbusier’s cité radieuse as well as to the urban utopias of Frank Lloyd Wright. Concentrated developments of affordable housing surrounded by green open space designed for lower-income groups had also been one of the major objectives of the Bauhaus in Europe. The effort to combine such notions became particularly evident in Toronto in the case of several large-scale suburban developments.

—

ENTER OUR CONTEST! Tweet a photo of your favourite modern building in Toronto using #modernTO for a chance to win a signed copy of Christopher Armstrong’s Making Toronto Modern.

For media requests, please contact Jacqui Davis.

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.