Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

SANDINO’S NATION BOOK LAUNCH

TOMORROW! September 16th

7:30 PM

The Bookshelf (Green Room), Guelph

View map >

The University of Guelph International Development Speaker Series, in collaboration with MQUP and The Bookshelf, is delighted to host the book launch & lecture for Stephen Henighan’s

Sandino’s Nation: Ernesto Cardenal and Sergio Ramírez Writing Nicaragua, 1940-2012

The Bookshelf recently posted a discussion on its blog between Stephen Henighan and Carrie Snyder, author of The Juliet Stories (Anansi, 2012). The summer of 2014, which marked the 35th anniversary of the 1979 Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua, brought together the two Canadian authors in an email exchange about their memories of Sandinista Nicaragua in the 1980s.

The following is an excerpt from their discussion on the Bookshelf Blog.

CARRIE SNYDER: (…) Tell me a bit about yourself. How did you come to be in Nicaragua during that time? When were you there? How long did you stay? Where did you live and what specifically did you do while you there?

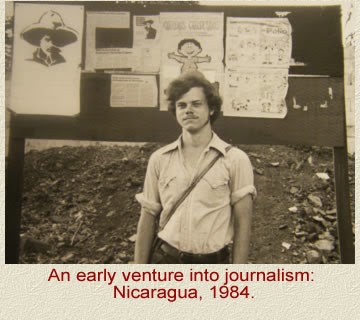

STEPHEN HENIGHAN: Like you, I got to Nicaragua via the USA. I think I’m about a dozen years older than you. I’m pretty sure my Nicaragua obsession would not have developed if I hadn’t left my home in the Ottawa Valley to do my undergrad work in Pennsylvania. I was already fascinated by Latin America, so I had read about the Nicaraguan Revolution in an Ottawa newspaper, but when I got to my college, Nicaragua was one of the two or three hot campus issues. It was on the front page of the New York Times every day. I fell in with a group of like-minded students, who were supported by activist profs. We learned everything about the Sandinistas: we knew all the debates and the ideological tendencies of the major figures, and read their essays or speeches or fiction or poetry. I came to the revolution through a mixture of literature and campus activism. I helped invite prominent Central Americans to campus (many were denied visas to enter the U.S.) and organized marches on Washington, D.C. to protest Reagan’s funding of the Contras. Finally, it became obvious that I had to make the trip myself. I went to Nicaragua in early 1984. By this time, I had studied literature and politics in Bogotá, Colombia and spoke fluent Spanish.

My political science professor helped me get accredited as a foreign journalist by the Nicaraguan government, even though I had never published any journalism outside the campus newspaper!

My political science professor helped me get accredited as a foreign journalist by the Nicaraguan government, even though I had never published any journalism outside the campus newspaper!

I spent time in Managua and in Estelí, in the north. In Managua I encountered the world of optimistic activists that you capture in The Juliet Stories: at rallies there were as many “Sandalistas”—hippie foreign radicals—as Nicaraguans. But the north was different. Very poor people there told me that thanks to the Sandinistas they had food and a house and health care and their children were learning to read. At the same time, the Contra War was much closer. You could see the hills where the fighting was happening. Another important event during my stay was my discovery of the Sandinistas’ policy of making books available to all at low prices. In Managua, I went to poetry readings by writers like Carlos Martínez Rivas and Gioconda Belli. I bought my first copies of books byErnesto Cardenal and Sergio Ramírez, the two writers whose careers form the narrative of Sandino’s Nation.

CARRIE: Our family also travelled north, to Estelí, Ocotal, and to Jalapa, even going to the Honduran border, a rural road essentially, where I remember putting my fingers into bullet holes left in trees from recent fighting. My Spanish was not yet very strong, but I had the distinct sense that the Nicaraguans whose homes we were visiting were nervous to have us there, and that we were being watched. That was the only time our parents took us that far north. We would stay in the homes of nuns or houses rented by Witness for Peace when we travelled, so even in places like Jinotega andChinandega, I was surrounded by Americans or other ex-pats.

Did you work as a journalist while in Nicaragua during that time? How long did you live there, or did you leave and return over a period of years? Did your opinions change during your time in Nicaragua?

STEPHEN: With my journalist’s card from the Sandinista government, I was able to attend debates at the National Assembly and interview whoever I liked. I did lots of interviews, including one with the Minister of Education, Fernando Cardenal. Unfortunately, I was still a really bad journalist. None of my articles got published. As often happens, I processed the experience better through fiction. Years later I wrote three short stories about the ideological contradictions of foreigners in Nicaragua that appeared in my first collection, Nights in the Yungas.

In fact, I was only in Nicaragua for about two and a half weeks in 1984. It seemed like much longer because my daily engagement with the country, in my reading, in my activism, in my discussions with friends, extended over the whole decade. I arrived there with a lot of prior knowledge: everything I saw seemed significant, from slogans to bullet-holes in walls to the profiles of the volcanoes and the smells that blew in off the lake. My impressions from that visit are indelible. I had lived in Bogotá, Colombia, a chilly, repressed, conservative society riven by civil war, where people trembled at the sight of a man in uniform. Nicaragua’s tropical exuberance blew me away. I gaped at the sight of young women in uniform necking with civilian boyfriends on street corners, of ordinary people chatting in a friendly way with soldiers on the country buses that I rode, of peasants lecturing me on their political opinions rather than remaining hunched and fearful. The only place where people seemed more muted was on a cooperative I visited near Estelí. I wasn’t surprised to learn, years later, that the cooperativization of agriculture had lost the Sandinistas supporters among peasants who had been hoping to receive private plots of land.

After I left, a lot of my friends went for shorter or longer stays, so I continued to feel like I was in touch through their reports and anecdotes By 1990, when the Sandinistas were defeated, I was living in Montreal. I felt as though an essential element of my imaginative universe had dissolved. I couldn’t imagine “returning” to Nicaragua because in my mind there was no longer a Nicaragua, as I had known it, to return to.

IMAGES from Sandino’s Nation on our Tumblr

To learn more about this book, click here.

For media requests, please contact Jacqui Davis.

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.