Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

In Autobiography of a Garden, Patterson Webster recounts her twenty-five-year gardening journey on the 750-acre property called Glen Villa in Quebec. The recently-published book explores the meaning of a garden, the ways in which we can learn from the land, and how we might preserve and present its history and the history of the peoples who once lived and grew there. Throughout, Webster describes the process of creating a garden, and the inseparable connection this process creates. The bond between garden and gardener is framed through ideas of growth and death to not only present the romantic beauty of the landscape but also the honest reality that is the passage of time.

In Autobiography of a Garden, Patterson Webster recounts her twenty-five-year gardening journey on the 750-acre property called Glen Villa in Quebec. The recently-published book explores the meaning of a garden, the ways in which we can learn from the land, and how we might preserve and present its history and the history of the peoples who once lived and grew there. Throughout, Webster describes the process of creating a garden, and the inseparable connection this process creates. The bond between garden and gardener is framed through ideas of growth and death to not only present the romantic beauty of the landscape but also the honest reality that is the passage of time.

Below, Webster describes her ever-changing relationship with the gardens at Glen Villa – from her first introduction to her hopes about the future. In the end, she asks what is more wonderful than the duality of land, earth and life: both fleeting and infinite.

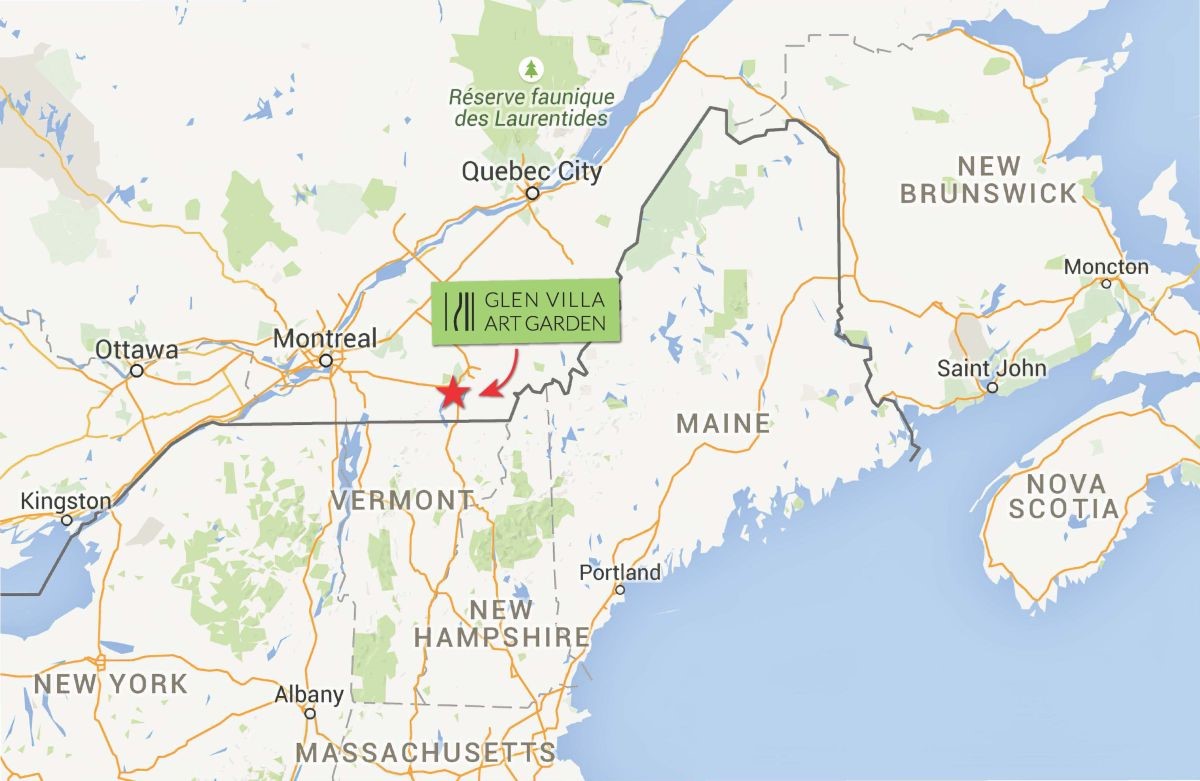

Twenty-five years ago, I began to create a garden at Glen Villa, a country property in the Eastern Townships of Quebec. Although I thought of myself then as a gardener, I was actually a neophyte, newly planted in a new land. I knew the names of ordinary plants and followed standard rules about how to use them, but I had no ideas of my own.

Glen Villa, Eastern Townships, Quebec, Canada.

Shortly after our family moved into the house, I began to work on the garden. I wanted to change the existing one, to make it mine, but I didn’t know how. What should the garden look like? What should it say – about the house, the land, or me and my family?

I knew it would say something, because every garden can speak. Every garden has a story to tell, and if we take the time to listen, we can hear it. Some gardeners tell their garden’s story through their choice of flowers, using aesthetics as the guiding principle. Others, concerned about the environment, focus on plants that attract pollinators or encourage biodiversity.

I share these concerns. Yet despite wanting a beautiful landscape that is ecologically beneficial, neither is the story that the garden at Glen Villa relates. Its story is about history and, by extension, about the passage of time.

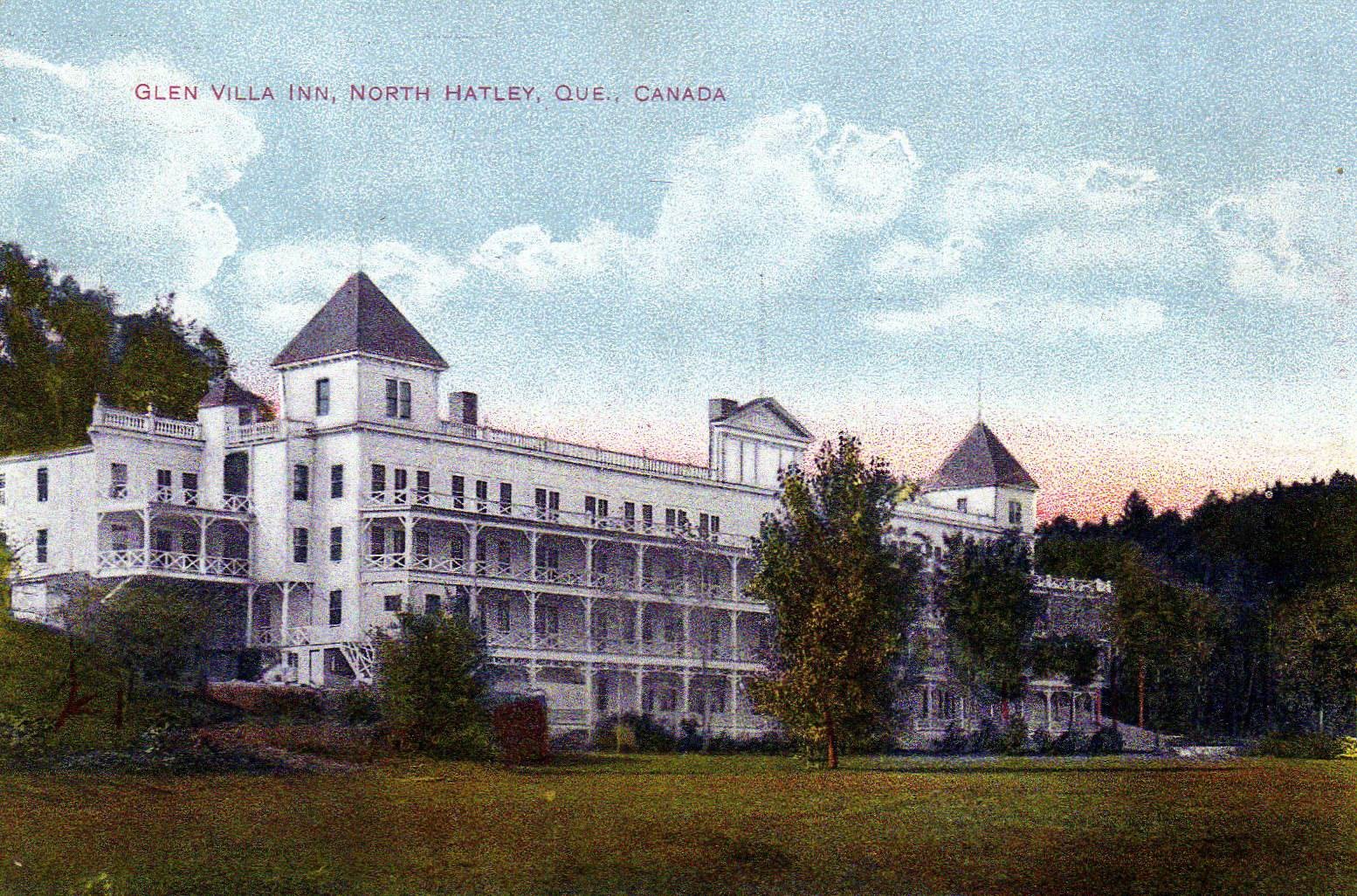

The name Glen Villa harkens back to Glen Villa Inn, a summer resort hotel built on the site in 1902. It was a grand hotel, attracting visitors from across North America. In a brochure about the hotel, the owner bragged it was located in the perfect environment, “free from malaria and hay fever. Void of mosquitoes and black flies. No fog, no mist.” Reflecting his desire to attract a wealthy clientele, he added that the hotel was “sufficiently removed from large city centres and the excursion element to assure refined patronage.”

Glen Villa Inn, circa 1905, shown in a postcard privately printed for G.A. LeBaron. Photographer unknown.

The hotel may well have offered all those things, but not for long: Glen Villa Inn burned down in 1909 and was never rebuilt. When we acquired the property decades later, the foundation wall still existed, one of many signs of the past that remained. In fact, everywhere I looked, I saw bits and pieces of history: the remains of an old mossy well that once supplied water to a summer cottage, rocks piled haphazardly by early settlers when they cleared the land, a straight line of ancient maple trees along the bank of the lake. The maples weren’t the perfectly matched specimens that you find in nurseries today but mismatched trees, each with its own character, its own personal tale.

An old maple tree on the bank above Lake Massawippi.

Those trees spoke to me. They told me that the land had a story to tell, and that its story was more powerful and more significant than any garden I could create. I began to walk the land, observing its dangers as well as its beauty. And gradually, I moved away from thinking of the garden as a place to decorate and began to understanding that it was a living thing, with its own needs, its own design, its own distinctive physical and emotional characteristics.

The dam dates back to the 1870s.

Autobiography of a Garden tells the story of how a conventional country garden became unconventional, and how that transformation created a bond between me and the land that is so close that the story of the garden is inextricably linked to my own.

In the 1960s the American cultural geographer J.B. Jackson wrote an essay in which he said that landscape is history made visible. When I read that phrase, quite a few years ago now, I realized that it encapsulated what I wanted to do at Glen Villa. I wanted to make history visible. I wanted to find ways to connect the past to the present, visually and metaphorically, and I wanted to make that connection through art as well as through horticulture.

Temple Façade.

The garden and wider landscape at Glen Villa Art Garden are full of references to the past, and to the way the past has shaped the present and will continue to shape the future. The garden is a place of beauty but now it is much more: a repository of memories and a setting that connects those who look with thoughtful eyes to a world of ideas. Creating and cultivating a garden is more than the task itself, it is – or it can be – an attitude towards life. My garden has put me into a direct relationship with the reality of how life is generated and sustained and how fragile and fleeting it can be.

Listening to the land, telling its stories and the stories of the people who inhabit it, has strengthened my relationship to my surroundings. It has allowed me to look more deeply into the beauty and into the horrors of nature that surround us all. I’ve been working on the project for more than twenty years and I’m not finished yet. I doubt I ever will be. And isn’t that a wonderful prospect?

The two signs make the message clear.

Webster’s Column honours Norman Webster’s career as a journalist.

Patterson Webster is an experienced gardener, writer, artist, and popular speaker. She lives in the Eastern Townships in Quebec.

back to all news

back to all news

Congratulations on your achievement, Pat! I have long admired the creativity and drive behind your amazing garden. So happy to see that your book about its creation is already receiving such well-deserved recognition.