Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

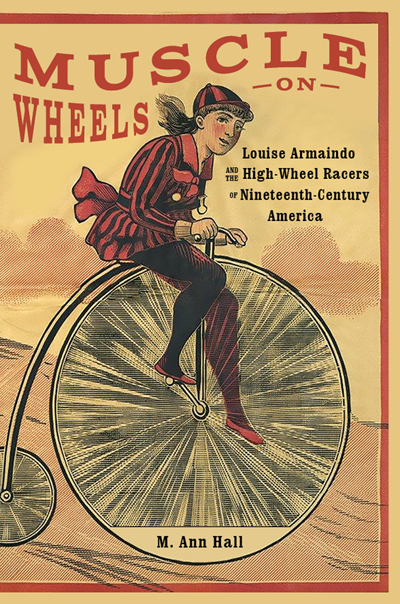

In the post below, M. Ann Hall elaborates on the writing and research process behind her new book, Muscle on Wheels: Louise Armaindo and the High-Wheel Racers of Nineteenth-Century America.

In the post below, M. Ann Hall elaborates on the writing and research process behind her new book, Muscle on Wheels: Louise Armaindo and the High-Wheel Racers of Nineteenth-Century America.

Among Canada’s first women professional athletes and the first woman who was truly successful as a high-wheel racer, Louise Armaindo began her career as a strongwoman and trapeze artist in Chicago in the 1870s before discovering high-wheel bicycle racing. Initially she competed against men, but as more women took up the sport, she raced them too. Although Armaindo is the star of M. Ann Hall’s new book, Muscle on Wheels, it also includes other women cyclists and the many men—racers, managers, trainers, agents, bookmakers, sport administrators, and editors of influential cycling magazines—who controlled the sport, especially in the United States. The story of working-class Victorian women who earned a living through their athletic talent, Muscle on Wheels showcases an exciting moment in women’s and athletic history that is often forgotten or misconstrued.

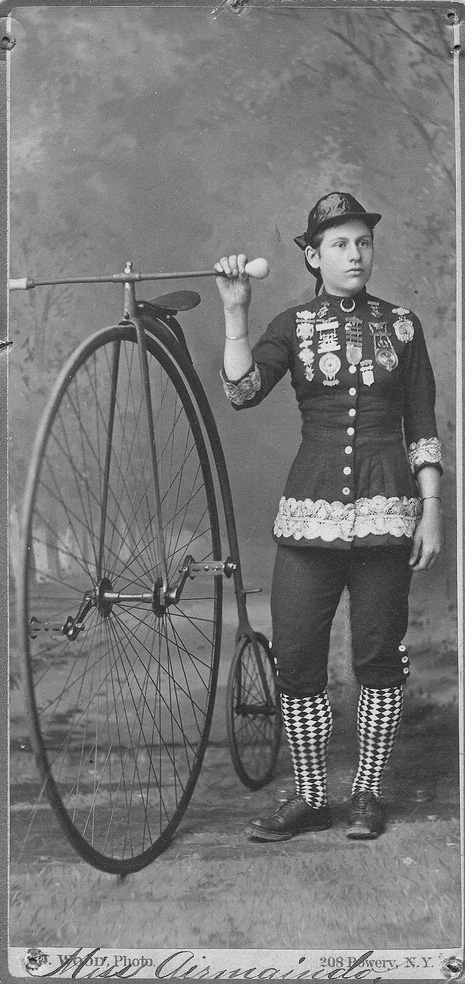

When I tell people that women rode and raced high-wheel bicycles (sometimes called “penny-farthings”) way back in the 1880s, they are astounded. Their first response is to ask how women got up on those machines. The average high-wheel was between 48 and 60 inches in height depending on the length of the rider’s legs. Most women racers rode a 51-inch wheel and mounting required considerable skill. Riders grasped the handlebar, placed one foot on a peg above the back wheel, then scooted the bicycle forward to gain momentum and quickly jumped up onto the seat while continuing to steer the bicycle and maintain balance. Obviously women could not do this in long skirts. Women racers usually made their own racing costumes – often tights or knickerbockers with a brightly coloured, tight-fitting jacket and jockey cap to match.

A rare photo of Louise Armaindo taken by the photographer John Wood of 208 Bowery, New York City, c. 1883 (Author’s collection)

I wrote Muscle on Wheels to learn more about Louise Armaindo, whose real name was either Louise or Louisa Brisebois. I’ve been researching and writing about Canadian women’s sport history for more than twenty years. It became clear that Louise was among Canada’s first women professional athletes, and she has been almost totally forgotten. A French Canadian, originally from a small community near Montreal, she is virtually unknown even in Quebec and has never been properly recognized for her achievements. Nearly 140 years after she became a marvel of athletic strength, talent, and endurance, Louise continues to be ignored by cycling historians and by those writing about women’s sport history.

Tracking Louise throughout the last two decades of the nineteenth century led me to examine the high-wheel era more closely. As a result, I discovered about twenty women in the United States who were professional high-wheel racers during the 1880s and early 1890s. For much of her career Louise raced against men, and she did so successfully, especially if given a handicap or head start. As more women entered the sport in the late 1880s, they challenged Louise, by then older and past her prime but still capable of winning. They performed before large audiences and earned a living, precarious as it was, through their athleticism.

The widely held belief that women first took up cycling with the 1880s introduction of the chain-driven safety bicycle and its more comfortable pneumatic tires often leads cycling historians to characterize the high-wheel era as masculinized and the safety era as feminized. True, it was mostly middle- and upper-class young men who rode the high-wheel for sport and recreation, and certainly bourgeois women did not. However, this masculine/feminine characterization ignores obvious class divisions and renders working women’s incredible athletic activity in the high-wheel era invisible.

I hope Muscle on Wheels will change these perceptions, so Louise Armaindo and other women high-wheel racers will be recognized as true pioneers of women’s cycling history.

M. Ann Hall is professor emerita in the Faculty of Kinesiology, Sport, and Recreation at the University of Alberta.

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.