Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

Last week our MQUP colleagues, Ryan Van Huijstee and Elena Goranescu, attended the event in Ottawa announcing the completion of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Here are Ryan’s observations:

The words “moved” and “moving” were used frequently over the last week to describe the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s final report entitled Canada’s Residential Schools. These words are certainly appropriate, but I worry this description limits our understanding of the range of powerful feelings experienced by those in attendance and those watching and listening throughout the lands and communities that form this country. The event may have been cathartic, but it should not be presented as closure.

The magnitude of the suffering and lingering effects, of the systematic neglect, and of the individuals and institutions involved can appear too enormous to comprehend, but the commission’s report is comprehensive. Given the urgency of the issues it raises, haste is required in reporting on the commission’s final report, which inevitably overlooks the scope of its work. How can anyone address it all? The quantifiable numbers are telling (150,000 victims attended schools; at least 3,200 confirmed children died; 6,000 survivors testified), but the report also acknowledges other effects cannot yet be quantified. How many other children died? How many experiences have we been unable to hear due to premature deaths or an understandable reluctance to speak about traumatic events? How can we trace the effects of the system to systemic problems in present-day Canada?

I was fortunate to attend the public event in Ottawa on December 15th and listen to speeches from each of the commissioners, survivors from across the country, the prime minister, the grand chief of the Assembly of First Nations, and officials from Christian denominations that operated many of the schools. Being there provided an opportunity to see the broader range of responses to the report than can be reported in the media. Yes, we were moved in the way we first think of when we hear this word. Whenever a speaker hesitated to hold off tears, the crowd took up their crying. At times an audible wail would rise from someone in the crowd and remind us of the individuals still directly affected by the legacy of the schools, and the friendships and possibilities that can be formed through shared grief and sympathy.

We were not only moved by the sadness of sombre commemoration and by the stark reality of more than a century of what the commission justifiably calls cultural genocide. We were moved to feel hope and cautious optimism. We were moved to doubt whether those in positions of power will seek to redress longstanding offences or address the commission’s ninety-four calls to action. There are many who are moved understandably by disappointment and anger. We were moved by a feeling of resilience by hearing more languages than English and French. (The report, already released in English and French, will eventually be released in Mi’kmaq, Ojibwa, Inuktitut, Cree, and Dené.) And we were moved to applause and to cries of celebration.

One thing that struck me was the genuine rapport and intelligent banter of affection and respect between the commissioners and the Survivor Committee that often moved us to laughter. (There was talk of humour as a coping mechanism and I can’t help but think of the final report as a survival mechanism for Canada.) John Banksland drew attention to the parka he wore to the ceremony. He told us he would have been punished for wearing it during his fifteen years in residential school. With a pause for effect, he added, “it’s a fancy parka, too.”

A wisecrack from Eugene Arcand (who spent ten years in residential school) revealed how difficult it must have been to arrive at the truth this commission reports. He said that at times there was nothing more that he wanted to do than to “bannock slap” Justice Sinclair, who responded with a laugh, a smile, and a wagging finger. This moment of candour about disagreements, this laughter through tears, and this willingness to listen and to talk about the horrors Canadian governments and churches forced on children to wilfully decimate entire cultures must also reveal a way forward and an example to follow towards reconciliation. The truth was difficult to arrive at, but reconciliation will require those involved to recognize and accept different emotions and needs with compassion. The whole range of human emotions were with us and all of them were valid. They should remain so as the country contemplates this report.

Let us hope that all the ways in which we were moved by the testimony of survivors and by the findings and recommendations of the commission move the country away from this past by addressing ongoing wrongs. In Winnipeg, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation will ensure that the report is not the last word on the subject, and will contribute to what Justice Sinclair has said is a new era. Throughout the day in Ottawa, I was struck by how many people greeted each other with sounds expressing surprise and joy at seeing each other there. These reunions brought the country together and I hope the commission’s report continues to join together the parts of our society that had been artificially divided by the schools.

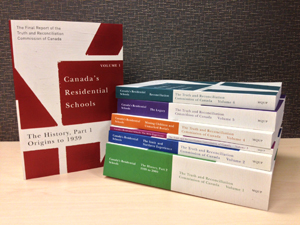

Since July, McGill-Queen’s University Press has worked with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to prepare the final report for its release and I have been fortunate to see the report before its release last Tuesday. It is a monumental work ordered around six thematic volumes and published in seven separate books – and there were several jokes about its weight of twenty-five pounds! Yes, it is long, much like the six-year process required to obtain the truth it presents. Undoubtedly the process of reconciliation will take time, too.

As broad as the range of responses to it, the report coveys the complexities of the system, but in an accessible prose that focuses on themes that will ensure understanding. It’s all there: how the schools were established; how they were run; how the schools affected the lives of the children who attended and their families; how many schools burned down because they didn’t meet safety standards; how children were starved and how nutrition rules were ignored; how a tuberculosis crisis swept through the schools; the reasons why the schools failed to provide the

education that was promised to their students; how children ran away; how people opposed the schools; how people alerted governments to the schools failures; the appalling punishments; how churches resisted the  schools’ closures. But the facts conveyed in the first four volumes (the history, in two parts, the Inuit and Northern experience, the Métis experience, and the volume addressing missing children and unmarked burials) are not the end of the report. The fifth volume outlines the lasting effects of the schools and the sixth volume presents a framework for reconciliation.

schools’ closures. But the facts conveyed in the first four volumes (the history, in two parts, the Inuit and Northern experience, the Métis experience, and the volume addressing missing children and unmarked burials) are not the end of the report. The fifth volume outlines the lasting effects of the schools and the sixth volume presents a framework for reconciliation.

The report is a masterful example of how to transcribe oral testimony, and an achievement that demonstrates the heights of careful and substantiated scholarly study. The commissioners described how humbled they were to have worked with so many survivors in preparing the final report. Everyone involved should also feel proud. I hope everyone who reads it will feel gratitude that we now have an unflinching account that points to the truth and points out a new direction.

As part of a non-profit scholarly press, it is not professionally appropriate for me to editorialize about specific recommendations, but it is the responsibility of everyone working in publishing to help disseminate the work of those we publish. I return to my previous question, how can we understand the magnitude of the residential schools and their effects? I can only urge you to take the time to face the history of the residential schools and the well-demonstrated legacy of the residential school system in this report. I don’t know how the commission did it, but they did. I’ll say it once for each book (in the imperative tense, but with the hope we can someday use the past tense): read it, read it, read it, read it, read it, read it, read it.

Ryan Van Huijstee

MQUP Managing Editor

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.