Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

The following excerpt from Paul-Émile Borduas, by François-Marc Gagnon, translated by Peter Feldstein, is on the controversial Refus global manifesto of 1948.

—

The pamphlet known as Refus global was the culmination of a long period of planning. It appeared on 9 August 1948 on the shelves of the only bookseller (whose name, ironically, was Henri Tranquille) brave enough to offer its incendiary prose to customers.With a print run of 400 copies, mimeographed on rough unbound paper, and a price of $1.00, it sold out quickly.

Between the covers (adorned with a Riopelle watercolour) is a collection of Automatiste texts, most importantly the eponymous opening piece “Refus global” (Total Refusal), as well as “La Danse et l’espoir” (“Dance and Hope”), by the dancer Françoise Sullivan, three plays by Claude Gauvreau – Au Coeur des quenouilles (In the Heart of the Bulrushes), L’Ombre sur le cerceau (The Shadow on the Hoop), and Bien-être (The Good Life) – “L’Oeuvre picturale est une experience” (“Pictures Are Experience”) by Bruno Cormier, and a proclamation by Fernand Leduc, “Qu’on le veuille ou non” (“Want It or Not”).

The “Refus global”manifesto itself was authored by Borduas and co-signed by fellow Automatistes Magdeleine Arbour,Marcel Barbeau, Bruno Cormier,Marcelle Ferron, Claude Gauvreau, Pierre Gauvreau,Muriel Guilbault, Fernand Leduc, Thérèse Leduc, Jean-Paul Mousseau, Maurice Perron, Louise Renaud, Françoise Riopelle, Jean-Paul Riopelle and Françoise Sullivan. Borduas also contributed “En regard du surréalisme actuel” (“About Today’s Surrealism”) and “Commentaires sur des mots courants” (“Comments on Some CurrentWords”). I shall focus on the parts of the pamphlet written by Borduas, as the other Automatistes’ contributions are more properly considered in a book devoted to the history of automatism proper.

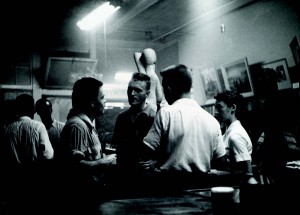

Opening for Refus global at Librairie Tranquille, 1951. From left to right: Claude Gauvreau, René Hamelin, Jean-Paul Mousseau, Dyne Mousseau.

To understand the impact Refus global had in 1948, it is essential to understand the sociopolitical context into which it was launched.While some Quebecers, such as many of those involved in artistic movements discussed in earlier chapters, had been exposed to intellectual currents from the outside world,most of Quebec society at the time was still dominated by what Marcel Rioux has called the “conservative ideology”:

This vision defines the Quebeckers as a group possessing a culture, i.e., a group which has a noble history, which has become a minority in the nineteenth century, and whose duty it is to preserve the heritage which it has received from its ancestors and to transmit this heritage intact to its descendants. The essence of this heritage is the Catholic religion, the French language, and an indeterminate number of traditions and customs. This vision looks to the past as the perfect time.

While such an outlook may have been understandable in 1840 in the aftermath of Lord Durham’s report – the French-Canadian community had turned inward when faced with the prospect of the assimilation he recommended – with time the conservative ideology had lost its force, if not its raison d’être. However the values the report noted as responsible for the continued presence of French Canadians as a definable group – the French language, Catholicism, and an ill-defined cluster of folkloric customs purportedly derived from peasant ancestors – had become enshrined in the Québécois mind as essential elements of French Canadian identity that must be preserved at any cost. Continual repetition of the same themes had ended by stifling creativity. Most critically, the conservative ideology discouraged contact with the outside world – the universe stopped at the edges of our forest clearings; all outside was darkness. Better to stay at home, among people who thought like you, in self-satisfied isolation. French Canadians had the Catholic faith, which guaranteed that they were on the path of absolute truth. They spoke French – not as well, perhaps, as some scholars might like, but French language congresses and societies were looking after that, weren’t they? Finally, they had the common sense of the peasant, the habitant. What more did they need?

(…)

The conservative ideology began to give way to what Rioux calls an ideology of confrontation or rattrapage (catching up). The static vision of a Quebec in thrall to its glorious past was discarded. In its place came a new vision in which the province emerged from its torpor, realized how far it had fallen behind in every field of endeavour, and proceeded to catch up with what was happening outside its borders. As they became aware of this new ideology, Quebecers began to feel ashamed, bitter towards their elites, and generally disaffected with the prevailing societal values. At the same time, there was a new openness to the outside world, a distinct appetite for novelty, a tendency to idealize what those outside Quebec were doing. When in “Refus global” Borduas sees “revolutions and distant wars,” the “pearly drops oozing through the walls,” “travel abroad” (especially to Paris), and “banned books” as signs of change and grounds for hope, when he sets the work of the poètes maudits against the “tired old refrains heard in this land of Quebec,” he is expressing a sentiment consistent with the ideology of rattrapage: if you are looking for the light, look elsewhere. And when he cries, “To hell with holy water and the French-Canadian tuque! Whatever they once gave, they have taken back again, a thousandfold,” he encapsulates the old values of the contested ideology and rejects them en bloc, admittedly with greater vehemence than was customary in his day but very much in the denunciatory vein of the new ideology.

To learn more about Paul-Émile Borduas, or to order online, click here.

For media inquiries, contact MQUP publicist Jacqui Davis.

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.