Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

MQUP author Douglas Hunter delves into the subject of his latest book, Beardmore: The Viking Hoax That Rewrote History. The book offers an unparalleled view inside a major museum scandal to show how power can be exercised across professional networks and hamper efforts to arrive at the truth. Hunter holds a PhD in history and has written several books including The Place of Stone: Dighton Rock and the Erasure of America’s Indigenous Past.

Our perception of hoaxes involving museums and art galleries tends to adhere to a standard script. A clever forger dupes the professional staff and nets a handsome windfall; an even cleverer detective exposes the fraud and brings the perpetrator to justice. The motivation for the fraud is usually financial, but sometimes the fraudster wants to have one over on elite arbiters of taste – or at least says he does.

This standard script bears no resemblance to the hoax that caused the contents of a purported Viking grave near Beardmore in northern Ontario to be displayed in the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) from 1938 to 1956. For one thing, the relics were authentic: it was how and where they were found that was the hoax. Piecing together this scandalous episode in the history of one of the world’s great museums took me several years, and as I sifted through documents in archives across North America, I realized there was no clever perpetrator, or clear victim—other than the public. Schoolchildren were taught the discovery in textbooks and on museum tours, and people in general absorbed a fraudulent version of the original European outreach to the Americas. If anything, the outward victim, the museum, turned out to be as much the perpetrator.

The story of the Beardmore relics is really two stories. One is of how Eddy Dodd, an itinerant prospector and low-grade con-man, managed to acquire a set of authentic tenth-century Norse relics and sell them to the ROM with a tale of having unearthed them in a mining claim a few miles east of Lake Nipigon. The other is how Charles Trick Currelly, the esteemed director of the ROM’s archaeology division, and his scholarly allies not only fell for such a crude hoax, but also actively enabled it, and kept it alive for so many years.

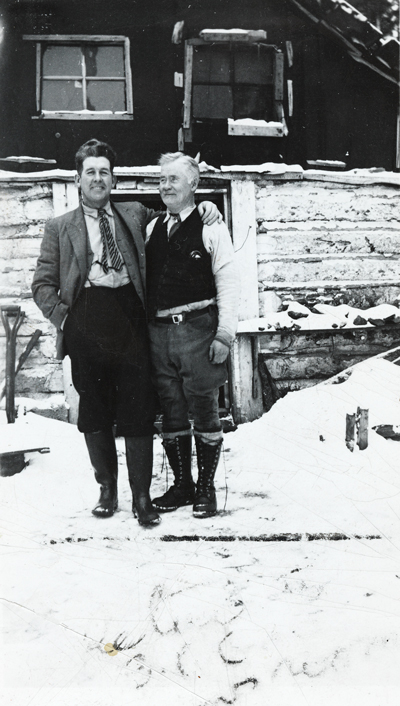

Fletcher Gill (left) and Eddy Dodd at the Beardmore middle-claim cabin, date unknown (ROM 12.9.2.5; ROM2018_16184_1)

The outward perpetrator, Eddy Dodd, probably never wanted to sell the relics. He simply may have hoped to attract interest in his mining claim as he showed them off, with an ever-changing story of how and when he found them. But an impoverished Dodd became desperate for Depression-era cash and Charles Trick Currelly was desperate to own the relics, and to believe in their authenticity. After agreeing to sell the relics, Dodd found himself in the presence of learned men who became intractably invested in keeping a crude scam alive for their own sake, not Dodd’s.

One of the most striking things about the Beardmore story to me was the scholarly world’s chronic unwillingness to challenge publicly Currelly’s sensational acquisition, which is why I am reluctant to list it among the hoax’s victims. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, it was left to a high-school vocational teacher, O.C. (Teddy) Elliott, and a renowned government geologist, T.L. Tanton, working in their spare time with their own money, to poke holes in the troubled provenance of the Beardmore relics and attempt to have the claims about the discovery overturned. Along the way, these two amateur detectives endured astonishing obstructionism from Currelly and his allies; the general press, deferring to the outsized reputation and opinion of Currelly, ignored their efforts to expose the hoax. Only in the mid-1950s, when a crusading anthropologist at the University of Toronto, Edmund Carpenter, took up the cause, did the hoax finally collapse. The Beardmore provenance was archaeological nonsense, but its defence was rooted in issues of class and credentialism, and in what Carpenter called “identification with institutional power.” Even after the authenticity case collapsed, Carpenter charged, some museum staff continued to defend the relics out of loyalty to the institution and the memory of Currelly.

While the hoax unravelled more than sixty years ago (and the ROM is a much different institution today, as is the archaeology profession), the Beardmore scandal nevertheless delivers timeless lessons about how elites can exercise power through professional networks, and how defending a scholarly position (and reputation) ultimately can become exercises of power to maintain that power.

Douglas Hunter holds a PhD in history and has written several books including The Place of Stone: Dighton Rock and the Erasure of America’s Indigenous Past. He lives in Port McNicoll, Ontario.

Learn more about Beardmore: The Viking Hoax That Rewrote History >

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.