Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

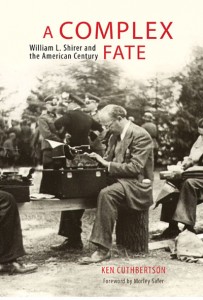

NEW RELEASE: Ken Cuthbertson’s new book, A COMPLEX FATE, is the first biography of William L. Shirer, one of the most provocative and influential American journalists of the twentieth century.

NEW RELEASE: Ken Cuthbertson’s new book, A COMPLEX FATE, is the first biography of William L. Shirer, one of the most provocative and influential American journalists of the twentieth century.

Shirer (1904-1993) was a prominent member of the legendary “Murrow boys”, a group of CBS journalists who gave their North American audiences a visceral sense of how Europe was spiralling into chaos and war.

With Shirer reporting live from inside Nazi Germany and Edward R. Murrow from blitz-ravaged London, the pair built CBS’s European news operation into the industry leader and, in the process, revolutionized broadcasting.

The following excerpt describes the tension and strict censorship that Shirer experienced in Berlin at the onset of the Second World War.

The moral battle lines between good and evil were drawn from the opening salvos of the Second World War. However, William Shirer found himself awash in conflicting emotions, dreading the coming bloodshed and devastation while also recognizing that Hitler was a madman who had to be stopped. On the night of 1 September, unable to sleep, Shirer tossed and turned in his bed as he contemplated the day’s events: “I felt a burning resentment against Hitler for so irresponsibly and deviously plunging [Germany] and Poland, and no doubt the rest of Europe, into a war which … would be much more murderous than the last.”

Where Shirer and many of his colleagues erred was in continuing to assume that when faced with the combined might of the Allies, Hitler would back down. If not, most observers felt Germany would be defeated in a short, bloody war. However, German officials assured Shirer on 5 September, five days into the conflict, that not a single shot had been fired there. As proof, Shirer and NBC’s Max Jordan were invited to visit the French-German border to see for themselves and to make sound recordings, for future use in their broadcasts. “American networks won’t permit [this],” Shirer lamented in his diary, “a pity because it is the only way radio can really cover the war … I think we’re throwing away a tremendous opportunity, though God knows I have no desire to die a burning death at the front.”

Shirer also knew how pointless any rush to report on the war in Europe would be. Given the prevailing mood of isolationism in Washington, American involvement in Europe’s latest conflict was a possibility that Hitler and his henchmen had either overlooked or scornfully dismissed as being so unlikely as to be irrelevant. That was confirmed for Shirer when one evening, two months after the German invasion of Poland, he and a group of American journalists encountered Hermann Göring at a social function at the Soviet embassy. The head of the German air force was in a genial mood as he drank beer and puffed on a cigar. Göring, ever pompous, could not resist boasting about the successes of his Luftwaffe in Poland. Göring chuckled when Shirer asked if he was concerned about a recent decision by the American Congress to repeal the neutrality law that forbade the selling of American airplanes to other countries – Great Britain and France in particular. “I got the impression he had given the matter little thought … Unlike Hitler and Goebbels and Himmler, Göring obviously had no dislike of us American correspondents, no matter what our country did. He could not take America seriously as a military power.”

(…)

When things were going well militarily, Nazi officials tended to be reasonable, even cordial, in their dealings with foreign journalists. That was especially true where Americans were concerned. The German government operated what Shirer’s colleague Howard K. Smith described as “a posh restaurant for the foreign press,” and like Berlin’s most best private eateries – where only high-ranking Nazi Party officials and military officers dined – these government-run dining rooms were not subject to rationing, at least not in the early years of the war.

Shirer’s afternoon routine was a repeat of his mornings: to prepare for his nightly broadcast, he read more newspapers, made more telephone calls, and when possible he met with trusted informants. The latter was an activity fraught with danger. Shirer’s travel was restricted, and Gestapo agents routinely monitored his activities or did all they could to make him believe they were doing so. To be seen talking with the CBS man in Berlin was a perilous proposition for German citizens, unless the interview was pre-approved, and such permissions were not easily obtained.

It was even more difficult for Shirer to gain access to high-Nazi leaders. Hitler, himself, gave no interviews and was seldom seen in public, apart from his occasional speeches in the Reichstag. Asked by his CBS bosses “to broadcast a [word] picture of Hitler at work,” Shirer made numerous inquiries. His best efforts yielded but a few trivial details about the Nazi dictator’s workaday routine; one of the most intriguing bits of information was the fact Hitler enjoyed American movies; the romantic comedy It Happened One Night – the winner of the Best Picture Oscar in 1934 – reportedly was one of his favorites.

Despite the tight grip of government control, Shirer was endlessly resourceful and always found news to report. At 5 p.m. each day he attended the Propaganda Ministry’s second media conference of the day. Afterward, his habit was to make his way over to the German broadcast center to prepare for his second broadcast of the day. When he could not drive because of the blackout, he walked to the studio. Given his restricted vision, the blackout-darkened Wilhelmstrasse was not easy to navigate, especially in winter. With the wartime shortage of gasoline and public works trucks, snow was no longer being cleared from city streets, and footing was hazardous. “I’m not noted for my memory, and it took me three months to memorize the exact position of the [many obstacles] which lay along the sidewalk between my hotel and the subway station,” Shirer reported in a September 1940 article for Atlantic Monthly. “It was a rare night when I did not collide with at least one obstacle or flop headlong into a snow pile … If I had been walking fast and hit a lamp post, I would arrive at the studio with a lump on my forehead and a headache.”

When his day’s work was finally done, Shirer invariably made his way to the Ristorante Italiano, where he savored the food and companionship. Most nights, he was back in his room at the Adlon Hotel and in bed by 3 a.m. after another eighteen-hour day.

(…)

On numerous occasions, especially in the opening weeks of the war, Shirer reminded listeners of the parameters of his job. For instance, while reporting the sinking of the Athenia he explained, “I’d like to point out to you that I’m not here to try to report what is going on outside [of Germany]. My assignment is to tell you what news and impressions I can pick up here in Berlin.” A typical Shirer broadcast script was 700 words. His approach was informal, his tone conversational. Given the censorship and the technological restrictions under which he was operating – CBS still refused to let its correspondents use sound recordings – Shirer did not have access to voice clips from government or military officials, nor was he allowed to quote them directly or even to offer his own comments on the latest developments. At times, this created problems; the rule of thumb under which Shirer worked was that anything he mentioned in his broadcasts had to be news that had already been reported in the German media or that had been announced at a government press conference. As often as not, what Shirer left unsaid was as revealing as what he said. Like Ed Murrow, Shirer became adept at conveying information through the tone of his comments and the inflection of his voice. Regardless, his battles with the censors were now ongoing and at times heated. All scripts were vetted by two censors, who came from the Propaganda Ministry, Foreign Office, or military high command. However, as relations between the United States and Germany worsened, the level and intensity of scrutiny increased. A third censor joined the daily fray.

When Shirer’s overseers objected to the content of his scripts, as they often did, it was usually because of his wording. On one occasion, the Nazi censors simply refused to allow one of Shirer’s fill-ins (American newspaper reporters who skirted their employers’ policies and picked up extra income by going on the air using pseudonyms) to do a scheduled afternoon broadcast; the only reason given was that the report might create a “bad impression” among CBS listeners. The fill-in meekly accepted this; Shirer did not. Upon hearing of the incident, he confronted Harald Diettrich, the director of German radio services. When Shirer threatened to stop broadcasting altogether if such interference continued, Diettrich relented. Uttering soothing words, he explained it had all been a “misunderstanding.” Having made his point and won the day, Shirer returned to work.

The logistics of CBS’s broadcasts from Berlin are worth noting, at least in passing. Each week, Paul White in New York sent Shirer a list of his scheduled air times. There were two each day: a four-minute report that aired at the breakfast hour in North America’s Eastern time zone. The other, longer and more in-depth, was heard around dinnertime. For each broadcast, Shirer carried into the studio with him two copies of his approved script; one was his to read on air, the other was for the broadcast technician, who sat with a finger on the mute button that would end the report instantly if Shirer deviated from the approved wording.

About five minutes before the scheduled airtime, the German technician would begin transmitting a shortwave signal across the Atlantic on the predetermined frequency. “This is DJL in Berlin calling CBS in New York,” he would say. Once contact was made and the clocks at both ends were synchronized, everything was ready. At the exact moment in real time that the broadcast was to air, the technician would signal Shirer to start talking. “This is Berlin…” had become his signature introduction. When the allotted broadcast time was over, Shirer would end off with the words, “We now return you to the Columbia Broadcasting System in New York.”

With no way of hearing the conversation between New York and Berlin, Shirer relied on the cue he received from the control room technician. By necessity, the process of broadcasting from Berlin required splitsecond timing and was dependent upon the weather and atmospheric conditions. As one of Shirer’s associates pointed out, “We hoped we had caught the cues correctly. We never knew for certain unless there was a serious difficulty or error. We sat down before the microphone and spoke blindly.”

Things could and did go wrong. Sometimes cues were missed, and on at least one occasion, when a broadcast technician in Berlin hit a wrong button, part of a German opera was beamed to New York while Shirer’s CBS report went out to listeners in Germany. Another time, because the CBS and NBC early broadcasts were aired at almost the same time each weekday, the reports were mixed up and were heard over the wrong networks. By late 1940, a year into the war, broadcasting technology had improved. In Berlin, Shirer now wore headphones that enabled him to hear the CBS announcer in New York as well as the reports from other correspondents, including Ed Murrow in London.

(…)

Because Shirer’s German was excellent, he enjoyed an easy rapport with many of the military people he met, especially those from the navy. When he inquired about one of the huge warships he saw Kiel shipyard workers were constructing, an obliging naval officer informed him that the vessel was the infamous Bismarck, a mammoth battleship the Germans were confident would enable them to break the Atlantic naval blockade that the British were working to put in place. “So this was the mighty Bismarck! … The British would have liked to have my view, I mused. The Bismarck looked almost completed. A swarm of workers were hammering away on its decks.”

Shirer enjoyed a similar freedom of movement when he traveled to the front in the company of German army officers; he noted how they and the men in the ranks dined together in the communal mess hall. Shirer also saw that officers fraternized with their subordinates and were willing to listen to their ideas and complaints. The effect of this openness and camaraderie was that morale in the Wehrmacht was high, and the men appeared to have bought into and accepted the regime’s rationale for the war. That, Shirer decided, helped to explain at least in part what he regarded as one of the great puzzles of the day: “These soldiers came from a country that had ruthlessly stamped out human freedom, savagely turned on its opponents, persecuted its Jews, whom it was planning to exterminate … How could these soldiers fight so enthusiastically for such a barbarous regime? I could not understand it.”

In the spirit of the Yuletide season (and because other correspondents had done similar reports), Shirer ended his late broadcast on Christmas night 1939 by having the crew of a U-boat sing “Stille Nacht” – “Silent Night” – to the accompaniment of an accordion. “Well, let’s look at the celebration on this ship,” Shirer told CBS listeners. “I think the boys want to sing.” After the broadcast, some of the German sailors approached Shirer to ask, “The English, why do they want to fight us?” Shirer could offer no answer to that question: “Evenings like that depressed me, and there were more than one that dark, bitterly cold winter.”

Shirer’s diary entries during this period reveal the extent of his despair and inner turmoil; there was scant joy in his life these days. A two-week Swiss ski holiday in February 1940 with Tess and Inga that provided temporary respite only served to remind him of how much he missed his wife and daughter; Inga was growing up without him. The familiar dark clouds over Shirer’s psyche reappeared when he returned to Berlin two days before his birthday. More and more, Shirer was questioning the direction of his life. His diary entry for 23 February 1940 reads, “My birthday. Thought of being 36 now, and nothing accomplished, and how fast the middle years fleet by.”

Nonetheless, he understood that self-pity was a luxury he simply could ill afford. The awareness that so many other men of his age were in uniform and had been swept up in events beyond their control was a sobering thought. So, too, was the realization that with the coming of spring, the war on the Western Front would heat up and many people would die. Shirer later reflected, “What had I to be sorry about?”

First CBS World News Roundup Broadcast on March 13, 1938:

To learn more about this book, click here.

For media requests, please contact publicist Jacqui Davis.

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.