Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

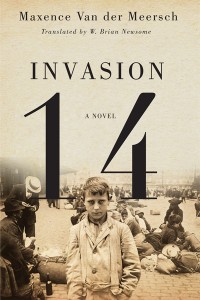

This year marks the centenary of two major events of World War I, the Battle of the Somme and the Battle of Verdun. To commemorate, why not add Invasion 14, an epic novel recounting the German occupation of northern France during World War I, to your summer reading list?

Based on personal experience, survivor testimony, and documentary research, Invasion 14 portrays the German occupation of northern France during World War I. The novel is set in Lille, Roubaix, and nearby villages along the Belgian border, with the front lines just miles away and the shelling routinely audible. An antiwar novel that goes beyond the trenches, this book is not about combat but its consequences, providing remarkable insights on the plight of French civilians and German soldiers as each group struggles to survive.

The following excerpt is taken from Chapter 1 of Invasion 14.

Jean Sennevilliers, the lime burner, left home for the quarry.

Jean Sennevilliers, the lime burner, left home for the quarry.

His house stood at the summit of Herlem Hill. To the east, one could see the entire village of Herlem, a ragged cluster of red and white houses crowded round a tall brick belfry with a slate-roofed spire. Beyond the village lay a sumptuous mass of tawny leaves, the splendour of a large forest, gilded by autumn, from which the regal towers of a château rose into view. This mansion belonged to the Baron des Parges, the owner of nine tenths of the land and farmsteads in the area. To the south, on a spur of the hill, was Fort Herlem: an old citadel with grassy embankments bordered by tall lines of poplars. Beside the fort, thick-set and huge, all bare walls and pointed roofs, Lacombe’s farmhouse sat nestled among barns, cowsheds, and stables. Lacombe was a rich farmer and the village mayor. Behind the farm and the fort, in the hazy distance and shadowed by a sinister cloud of soot, the cities of Roubaix and Tourcoing spread toward the horizon, fuming and bristling with smokestacks, reservoirs, and gasometers.

To the north, at the foot of the hill, the white rock was cleft by a large and steep ravine, a sort of gaping rift, which stretched and widened into the form of an enormous seashell. This was the Sennevilliers’ quarry. Hidden in its depths were the still waters of an emerald green pond, set in the white stone amid a confused mass of little willows and sturdy rushes serried along the banks. Halfway up the hill, one could see the kilns, types of square towers capped by extinguisher roofs, from which smoke rose gently into the tranquil air. The view, from this side, opened onto the endless Flemish plain. In the far reaches, one could just make out the hills of Messines and Kemmel, barely perceptible ripples set against the misty, bluish sky, and finally two white and almost indiscernible silhouettes – the tower of Cloth Hall and the steeple of the cathedral in Ypres.

This landscape was peaceful and showed no marks of war. But the villagers had already seen the Germans in September: a troop of Uhlans clothed in huge grey cloaks, with embossed shapkas of black leather on their heads; long lances, adorned with red and black pennons, resting in stirrup boots; and revolvers at the ready. They had advanced slowly, restraining their slender, spirited horses with new harnesses of tanned leather. The men were big, strong, young, with fine, ruddy complexions and athletic shoulders. Beneath their capes, long horizontal epaulettes further magnified their commanding appearance.

The Germans had locked all the men in the church and ransacked the house of Marellis, the tax collector, to find his cash box. Reservists from Lille had driven off the Germans, killing two of them. Lacombe, the mayor, had nailed the cloaks of the dead men to the door of town hall and divided the bloody tunics among the crowd.

Since then, the Uhlans had not returned.

Jean Sennevilliers went down to the quarry. Mobilization orders had just arrived from Lille. It was now the beginning of October. This time, the Germans were overrunning the entire department of the Nord. Since the first of September, the prefect of the Nord had been asking the General Staff in Boulogne for instructions about recruits, but in vain. He had been told to wait. Finally on 6 October the General Staff had sent the order to evacuate all available men. This order could have been delivered by car, dispatch rider, or telegram. It was put in the mail. The prefect in Lille received it three days later. By then the Germans were at the gates of the city. The prefect sent policemen, cyclists, and volunteers in all directions to announce the mobilization. People hesitated, sensing peril, but most men started off. Thus began a new exodus – after the one in September toward Dunkerque – of thousands and thousands of men toward the south of France and the unknown.

Learn more about Invasion 14: a novel

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.