Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

“Do you know my most beautiful memory? It was New Year’s Eve. To celebrate the new-year there were traditions. One of my mother’s traditions was she would open the door at midnight. All the surrounding factories would sound their whistles, the sounds of the factories. All the whistles would go off together, all the CNR trains and all the boats, the boats would go “Mmm.” And it would make a mysterious sound. And the trains going ‘gueding, gueding, gueding’. It created a very mysterious atmosphere. I can’t really describe it any other way. We were fascinated by the sounds. All the sirens, the firemen, all sorts of sirens would go off at midnight. A real celebration that was my neighbourhood.” – Élise Chèvrefils-Boucher

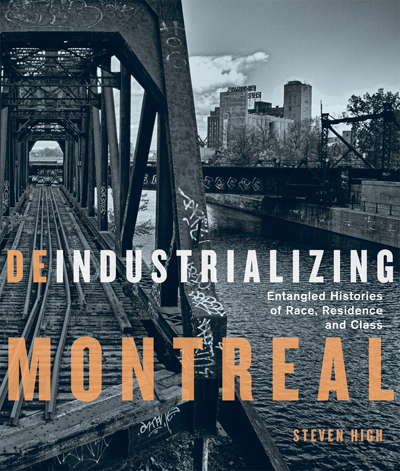

In his new book, Deindustrializing Montreal: Entangled Histories of Race, Residence and Class, Steven High looks at the intimate relationship between capitalism, class struggles, and racial inequality in two working-class Montreal neighbourhoods.

In his new book, Deindustrializing Montreal: Entangled Histories of Race, Residence and Class, Steven High looks at the intimate relationship between capitalism, class struggles, and racial inequality in two working-class Montreal neighbourhoods.

In the guest blog below, Steven High sheds some light on the history of Point Saint Charles and Little Burgundy.

Deindustrializing Montreal: Entangled Histories of Race, Residence and Class tells the story of two working-class neighbourhoods, one Irish and French, almost entirely white, and the other multiracial, the historic home of the city’s English-speaking Black community. Point Saint-Charles and Little Burgundy face each other across the Lachine Canal in what was once the most heavily industrialized urban area in Canada. Childhood memories of these factories, like the ritual of sounding in the new year, speak to the ways that class feeling infused people’s sense of place. This river of memory begins with a trickle in the first two decades of the twentieth century and flows right into the twenty-first. The history of urban deindustrialization is thus told through a multitude of stories and a myriad of voices. There are also more than 200 photographs.

By undertaking a cross-neighbourhood comparative history, this study invites us to consider the ways that race and class shaped and otherwise influenced the experience of deindustrialization in our metropolitan cities. Deindustrializing Montreal thus bridges the deepening divergence of class and race analysis and recognizes the intimate relationship between capitalism, class struggles, and racial inequality. Specifically, I turn to the concept of racial capitalism, which recognizes the extent to which racial differentiation and hierarchy are integral to class structures and urban geography.

Over the first half of the twentieth century, pervasive anti-Black racism in Montreal resulted in the exclusion of Black labour from factory employment. Instead, Black men found jobs on Canada’s railways and women were largely restricted to working as domestics in the homes of the wealthy. “In those days,” recalled Babsey Simmons: “there were no jobs for Colored men whatsoever, the only job for them was on the train, as a porter, which was a very demeaning job at that point in time. They were underpaid but they did their job with dignity.” The structuring force of racism thus led Black Montrealers to settle mostly in the northern half of what would become Little Burgundy, given its proximity to the city’s two main train stations.

Point Saint-Charles, for its part, developed as a white working-class area due to the hiring practices of local industries. However, it was a neighbourhood divided by a railway embankment that separated a mainly English-speaking south-end and a mainly French-speaking north. Long-time residents frequently spoke of the “other side of the tracks”. By all accounts, it was a “tough” working-class neighbourhood. Families were on a first name basis with neighbourhood factories such as “Northern,” “Redpath”, “Sherwin” and the CN Shops. It is said that there were once taverns on nearly every street corner. Because neighbouring Verdun was officially “dry,” this made Point Saint-Charles especially ‘wet.’

The decline of the two neighbourhoods began during the years of unionized prosperity during the 1950s and 1960s. Those who moved up, tended to move out: leaving the poorest behind. Then the factories closed. The total number of manufacturing jobs in the area fell from 28,000 in 1951 to just 7,000 in 1988. Montreal’s southwest lost half of its population between 1961 and 1991, a rate comparable to the hardest hit cities of the US Rust Belt. These were years of profound social crisis in the two neighbourhoods.

As the book shows, Point Saint-Charles was mainly left to rot by suburbanization and deindustrialization, until it was revalorized by gentrification, whereas Little Burgundy was torn apart by urban renewal and highway construction as well. This historical divergence had profound consequences in how urban change was experienced, understood, and now remembered. Stanley Clyke, the long-time executive director of the Negro Community Centre, reported in 1969 that: “It is said that urban renewal ‘does things to people.’ Urban renewal has only started in Little Burgundy, and already forces that have been at work among the population since its inception have set in motion thinking and action hitherto unheard of.” The transformation of the industrial canal into a leisure park, administered by Parks Canada, is an important part of the story as it provided vital green infrastructure for the gentrification of Montreal’s Sud-Ouest. How communities responded to the ongoing structural violence of these waves of change and represent this destructive history is the focus of the book’s final section.

Steven High is professor of history at Concordia University’s Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling.

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.