Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

In a year of many anniversaries, 2017 also marks 100 years since the passage of the first Federal progressive income tax act that was signed into law on September 20, 1917. To meet the financial pressures of World War I, the government of Robert Borden conceived of a direct tax on income which brought a level of ‘fairness’ to taxation of the citizenry and it was greeted with howls of outrage in part because the law infringed on the provincial right to tax directly. Issues around taxation have long stimulated political and social change and even revolt (“No taxation without representation.”); the history of Canada is no different. Elsbeth Heaman, in her new book, Tax, Order, and Good Government: A New Political History of Canada, 1867-1917 sets out to show how the history of the new nation of Canada was inextricably tied to taxation and the control of wealth. The following excerpt is one example of the ‘unsunny’ treatment of the poor and racial minorities when it came to collecting taxes.

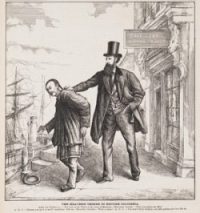

James Weston, “The Heathen Chinee in British Columbia” (Canadian Illustrated News, 26 April 1879) – Image courtesy of Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University

The Indigenous peoples and the Chinese in British Columbia encountered a very different tax regime than did residents of European descent, one marked by casual brutality that voters would not have tolerated. Tax collectors marched into Indigenous households with guns ostentatiously poking out of their back pockets and hunted down Chinese in armed bands that looked more like brigandage than law enforcement. Such behaviour was shocking then as now. The fight between Kirkup and the railway workers in 1881 ended in a confrontation that horrified one newspaper correspondent. According to a report: Captain Charles Todd proceeded up the railway with nine men whom he placed “in battle array, all well armed with first-class revolvers. This caused the Chinese to weaken, and becoming docile they paid their taxes like little men.” The letter writer, “Point Blank,” was outraged by the very principle of a head tax as both unfair and susceptible to fraud by collectors. But he was also outraged by the use of force: “Taxation is tyranny when the tax is collected with pistols.” It was a form of tyranny that Chinese and Indigenous peoples in BC knew all too intimately. Tax collectors kitted themselves out with symbols of violence to underscore their right and power to strip these impoverished peoples of their few belongings. The contact between taxpayer and collector approximated as nearly as possible pure coercion, without the cultural mediations that the liberal state ordinarily uses to conceal violence and without the discretion shown to other taxpayers. Taxation is normally a political negotiation designed to elicit consensus and an administrative process grounded in data and documentation; it is also, not incidentally, supposed to elicit revenue. Racialized taxation in British Columbia did none of those things well. There could be no consensus in the absence of political representation. Tax collectors refused to acquire data that would enable them to tax efficiently, preferring to denounce their quarry as evasive and unknowable because they were anomalous in their property relations. Furthermore, revenue was subordinated to domination, as can be seen from the explicit recognition that even those Chinese who were too poor to tax would, nonetheless, be forcibly and painfully taxed with all the coercive powers that the provincial state could muster, and then some. Ideological and cultural arguments remained closely intertwined with political and economic reasoning and with relations of power exercised intimately upon the bodies and properties of racialized populations.

[Excerpt from Tax, Order, and Good Government: A New Political History of Canada, 1867-1917, E.A. Heaman, pp. 115-16]

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.