Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

In Disparate Remedies: Making Medicines in Modern India, Nandini Bhattacharya details the cultural history of medicines in colonial and postcolonial India. In the guest blog below, Bhattacharya gives some important background information and introduces us to her new book.

In Disparate Remedies: Making Medicines in Modern India, Nandini Bhattacharya details the cultural history of medicines in colonial and postcolonial India. In the guest blog below, Bhattacharya gives some important background information and introduces us to her new book.

While researching for and writing Disparate Remedies, I had in mind India’s flourishing pharmaceuticals industry, which expanded exponentially in the late twentieth century. At present India exports their pharmaceuticals to around two hundred countries, which accounts for around half of the generic medicines imported in Africa. India also provides for approximately 40% of the demand for generic drugs in the United States, and a quarter of all medicine in the United Kingdom. This is apart from vaccines; Indian manufactures supply about 70% of the global vaccine demand. Add to this, billions of dollars in Ayurvedic and herbal therapies that are part of the global ‘well-being’ and alternative or complementary therapies industry.

My first query when researching my book was to figure out how all this was made possible. Conventional histories of Indian manufactures generally offer narratives of structural inequalities that hobbled indigenous industries until the end of British rule in 1947, and a too-tightly controlled government regime, vulnerable to corruption and abuse, (permit-license-quota raj) that allegedly restricted investment and innovation in the postcolonial era. These narratives usually situate the 1991 structural reforms when the Government of India opened up the Indian economy and restructured labor laws to facilitate international investment.

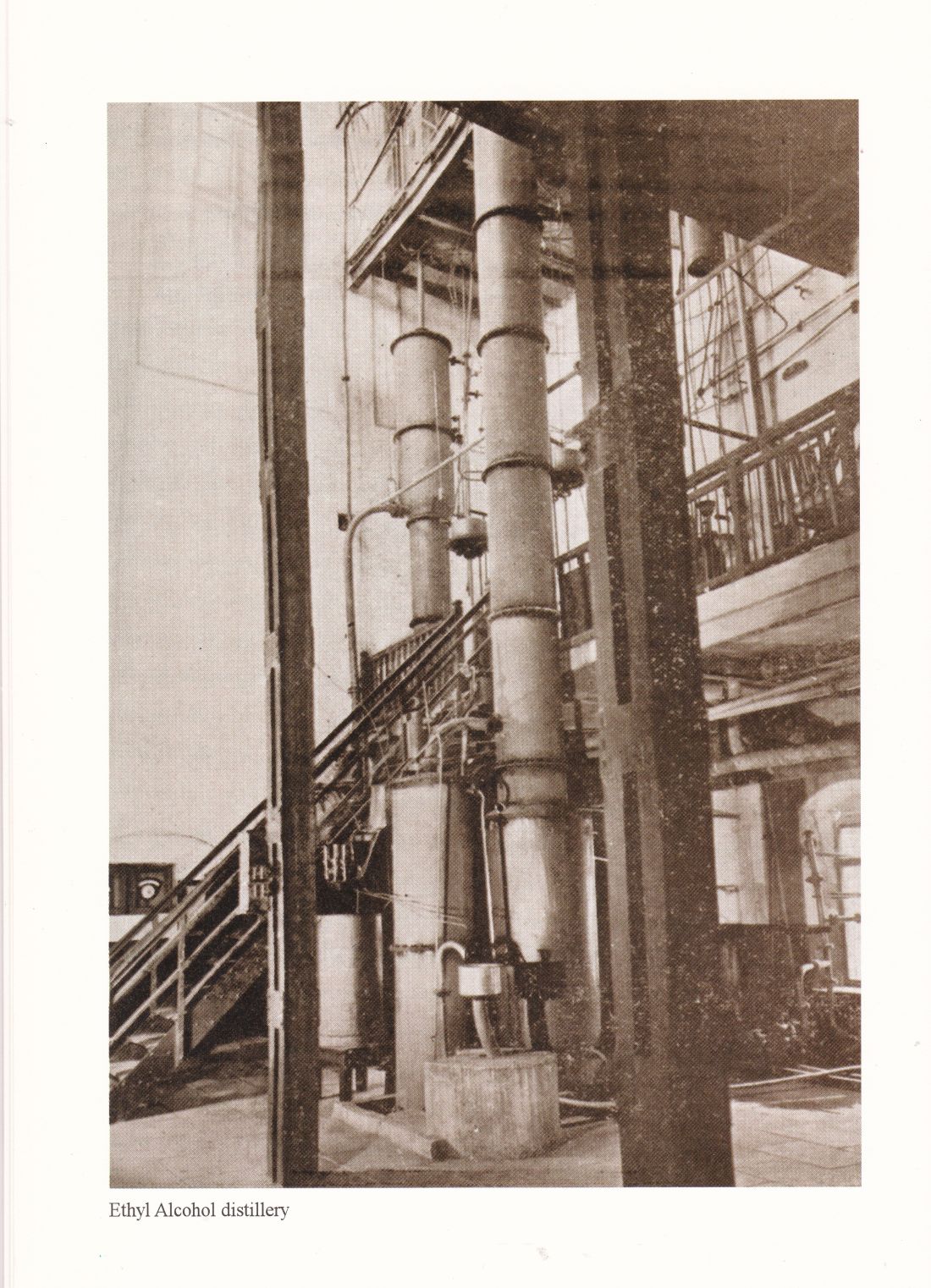

Figure 2.4 Ethyl Alcohol Distillery, ACWL, 2007

I was taken aback when I discovered that the fledgling Indian pharmaceuticals industry was a long-established one. It has a rich and textured history, like the better- known and studied milled cotton or leather goods manufactures in British India, and involves insights into British and European competition for the Indian market, the multi-layered ‘bazaar’ or indigenous manufacture and trade in drugs and therapies, tariff wars between home and colony, and Indian scientific innovation. The key to understanding the rise of the Indian pharmaceutical industry was to appreciate how it successfully incorporated disparate systems of production, marketing, and consumption of drugs.

As I delved deeper into the themes of the book, I realized that the terms historians of medicine have used to describe and differentiate between ‘indigenous’ or ‘western’ medicine were convenient ones, more suited to the historical medical systems and their epistemic study than to the medical commodities sold at the market. By studying both the consumption and the production of medicines in the Indian market, Disparate Remedies offers insights into a fragmented and eclectic medical culture, many elements of which have continued to the present day.

Figure 4.1 Sir W. Denison and others planting the first cinchona trees in the Nilgiris, c.1862

Figure 4.1 Sir W. Denison and others planting the first cinchona trees in the Nilgiris, c.1862

In the book I point out that the medical therapies manufactured and traded in colonial India, which often came to be regarded as ‘indigenous’ medicine were no different in their cognitive content to the imported British, European, and American-made ‘western’ medicines. Although the latter were processed and packaged differently, and appeared distinct, the so-called western medicines comprised similar botanical and mineral raw materials to indigenous medicines until the dissemination of sulpha drugs and antibiotics in the 1940s, and indeed, provided similar clinical outcomes. Generic ‘cholera pills’, ‘dysentery pills,’ or ‘blue pills’ (the last being mercury-based and used widely for syphilis) were manufactured internationally and locally and dispensed by both ‘scientific’/‘western’ and Ayurvedic and Unani medical practitioners.

What distinguished ‘scientific medicine’ (the term biomedicine came into use much later in the twentieth century) from indigenous therapies was their epistemic legitimacy, established by the international drugs industry, the western scientific community, and within modern India, legitimated and prioritized by the colonial state itself. Meanwhile indigenous medical systems were valorized in nationalist discourse. Nonetheless, as I argue in Disparate Remedies, it was not as unproblematic to link the greater use and support for indigenous therapies to the regeneration of the Indian nation as the homespun khadi cloth had been. This is because the Indian medical market was fragmented, where practitioners of traditional systems and adherents of the new industrialized medicine operated in sometimes fractious and competitive relationships, but often too in a symbiotic one. The question of legitimacy of indigenous drugs that were unofficially in use by all practitioners came to be mediated by the scientific category of identifying their active principles.

However, identifying the active principles of the hundreds of indigenous botanical drugs, with their regional variations and nomenclature, proved to be an endless and ultimately, unsatisfying affair. This was clearly the reason why the official, legally binding Indian Pharmacopeia was only established after independence, by which time the indigenous botanical drugs were made redundant by synthesized medicines and antibiotics. In spite of the nationalist rhetoric for indigenous medicine, the new nation-state in independent India privileged biomedicine. The public sector began manufacturing antibiotics and attempted (and eventually failed) to fulfil the nationalist expectations of the provision for cheaper high-quality medicines for the majority of citizens.

Finally, in Disparate Remedies I point out the difficulties inherent in transforming the nationalist aspiration of cheap medicines for all into active, practical life enhancing policies in the postcolonial arena. The Indian Patents Act (1970), which recognized product patents but not process patents, provided the foundation for the extensive generic medicines industry in present -day India. However, the high prices of quality drugs and the concurrent low income of much of the population enables a plural medical market to survive. Therefore, while India exports medicines to approximately two hundred countries, the access to cheap and safe medicines continues to be beyond the reach of large swathes of its own citizens.

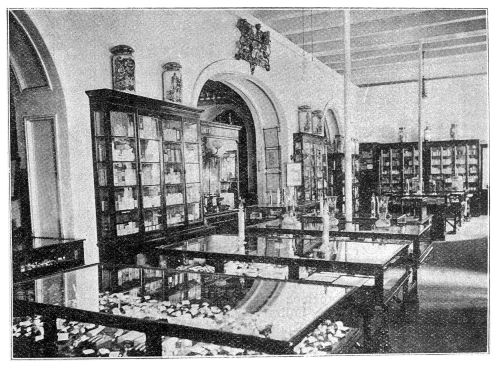

Figure 1.3 Inside the main retail store of Smith, Stanistreet and Company, Calcutta

This book makes two key points. First, the essential distinction in the Indian medical market, the book argues, is not between western or biomedicine and indigenous medicine; it is between those who can afford high quality medicines and those who depend on the unregulated, illegal, and dubious medical market in which the quality of cheaper medicines available is questionable, as are the qualifications of those diagnosing, prescribing and dispensing these medications.

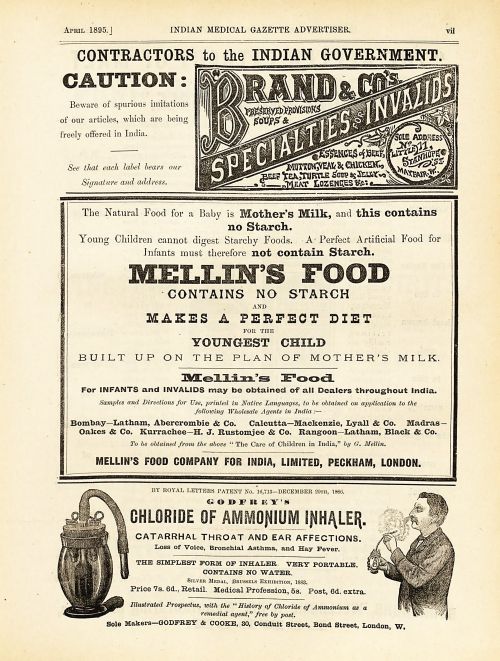

Figure 5.1 Advertisement for Mellin’s food (Indian Medical Gazette, April 1895)

Second, in showing this variegated and entangled medical culture, this book moves beyond the simplistic allopathic/traditional indigenous parsing of the medical marketplace in India of earlier historiography and places itself firmly in the most recent discourse in which historians have learned greatly from current work by social anthropologists and medical sociologists assessing the fluid pharmaceutical markets within and between India, China, Africa and South America.

Nandini Bhattacharya is associate professor at the University of Houston, Texas.

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.