Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

The following excerpt is from Peter Swirski’s From Literature to Biterature.

The following excerpt is from Peter Swirski’s From Literature to Biterature.

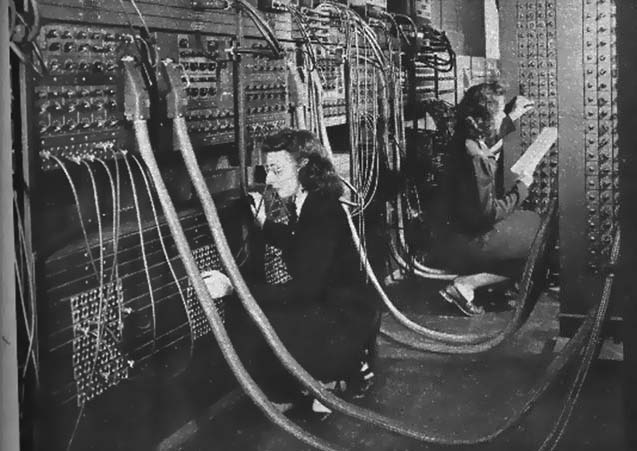

The first general-purpose – Turing-complete, in geekspeak – electronic brain was a behemoth of thirty-plus tons, roughly the same as an eighteen-wheeler truck. With twenty thousand vacuum tubes in its belly, it occupied a room the size of a college gym and consumed two hundred kilowatts, or about half the power of a roadworthy semi. Turn on the ignition, gun up the digital rig, and off you go, roaring and belching smoke on the information highway.

Running, oddly, on the decimal rather than the binary number system, the world’s first Electronic Integrator and Computer also boasted a radical new feature: it was reprogrammable. It could, in other words, execute a variety of tasks by means of what we would call different software (in reality, its instructions were stored on kludgy manual plug-and-socket boards). Soldered together in 1946 by John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert at the University of Pennsylvania, the eniac was a dream come true.

Soldered together in 1946 by John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert at the University of Pennsylvania, the eniac was a dream come true.

It was also obsolete before it was completed. The computer revolution had begun.

The rest is history as we know it. In less than a single lifetime, ever more powerful computing machines have muscled in on almost all facets of our lives, opening new vistas for operations and research on a daily basis. As I type this sentence, there are more than seven billion people in the world and more than two billion computers – including the one on which I have just typed this sentence. And, by dint of typing it, I have done my bit to make the word “computer” come up in written English more frequently than 99 per cent of all the nouns in the language.

In a blink of an eye, computers have become an industry, not merely in terms of their manufacture and design but in terms of analysis of their present and future potential. The key factor behind this insatiable interest in these icons of our civilization is their cross-disciplinary utility. The computer and the cognitive sciences bestraddle an ever-expanding miscellany of disciplines with fingers in everything from alphanumerical regex to zettascale linguistics.

(…)

Underwriting this new field is mounting evidence from the biological and social sciences that a whole lot of cognitive processing is embedded in our natural skill for storytelling. As documented by psychologists, sociobiologists, and even literary scholars who have placed Homo narrativus under the microscope, we absorb, organize, and process information better when it is cast in the form of a story. We remember and retrieve causally framed narratives much better than atomic bits of ram.

The power of the narrative is even more apparent in our striking bias toward contextual framing at the expense of the underlying logic of a situation. People given fifty dollars experience a sense of gain or loss – and change their behaviour accordingly – depending on whether they get to keep twenty or must surrender thirty. Equally, we fall prey to cognitive illusions when processing frequencies as probabilities rather than natural frequencies. A killer disease that wipes out 1,280 people out of 10,000 looms worse than one that kills 24.14 per cent, even though bug number 2 is actually twice as lethal.

Given such deep-seated cognitive lapses, the idea of grafting an artsy-fartsy domain such as storytelling onto digital computing may at first appear to be iffy, if not completely stillborn. Appearances, however, can be deceiving. The marriage of the computer sciences and the humanities is only the next logical step in the paradigm shift that is inclining contemporary thinkers who think about thinking to think more and more in terms of narratives rather than logic-gates. The narrative perspective on the ghost in the machine, it turns out, is not a speculative luxury but a pressing necessity.

This is where From Literature to Biterature comes in. Underlying my explorations is the premise that, at a certain point in the already foreseeable future, computers will be able to create works of literature in and of themselves. What conditions would have to obtain for machines to become capable of creative writing? What would be the literary, cultural, and social consequences of these singular capacities? What role would evolution play in this and related scenarios? These are some of the central questions that preoccupy me in the chapters to come.

Read more of Swirski’s thoughts on computhors in this interview.

To learn more about From Literature to Biterature, or to order online, click here.

For media inquiries, contact MQUP publicist Jacqui Davis.

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.