Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

Setting the Stage

The relaunched Queer Film Classics series has added a handful of films from the so-called Stonewall era to its miscellany of more recent queer films from the period between 1983 and 2014: namely the two American Best Picture Oscar winners Midnight Cowboy (1969; Towlson, 2023) and Cabaret (1972; Proulx, forthcoming) and the two roughly contemporaneous Quebec classics À tout prendre and Il était une fois dans l’Est (1963, 1974; Vaillancourt, 2023), also the prizewinning prides of a national cinema.

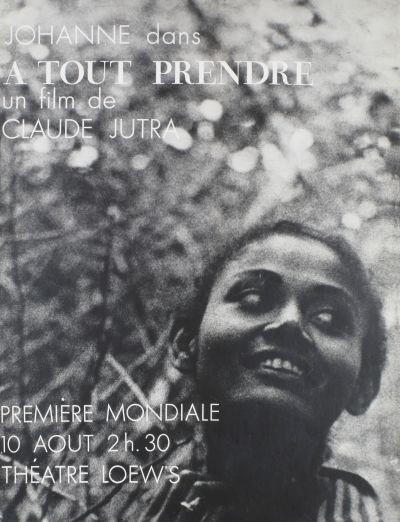

À tout prendre film poster, from the Festival du cinéma canadien (1963). Collection de la Cinémathèque québécoise 1997.0015.af.

The release or imminent release of these three new books on films that marked the dawn of gay liberation as a movement – and the crumbling of Production Code censorship and the peak of what became known as the sexual revolution – offered a chance for their authors to come together for a blog conversation about these films and that moment a half century or so ago that saw the emergence of queer cinema in its contemporary form, as well as queer art and literature in their broadest form. The Stonewall era occasioned a legendary creative fertility and enabled a new freshness for “fag stuff,” even in faraway Quebec.

What follows is a friendly, non-specialized conversation between a film critic, an art historian, and a film studies teacher and columnist that we hope will appeal to the series’ diverse readership. It has been edited for clarity.

Jon Voight on the cover of The Advocate (September 1969)

Sally sings the sex-positive power anthem “Mein Herr.” Cabaret, 1972. Film Still © 2018 Warner Archive Collection Blu-ray

Jon, Mikhel, and Julie, is there a canon of 2SLGBTQ+ cinema/culture that you see your book engaging with – strengthening? subverting? broadening? What is your current sense of the term “classic”?

Jon Towlson: My book tries to offer a fresh perspective on Midnight Cowboy by attempting to move past previous interpretations of the film as homophobic and problematic to focus instead on its relevance to queer friendship and queer experience. I see it as a proto-queer buddy movie and forerunner to later movies like Brokeback Mountain and My Own Private Idaho (and its portrayal of hustling and queer friendship has influenced international movies like the 2005 Israeli drama Good Boys). So, I would argue that it deserves a place in the queer film classic canon for those reasons!

Mikhel Proulx: As a non-film historian, I had assumed that Cabaret was firmly entrenched as a queer film classic. So I was surprised to learn that very few queer scholars have given the film serious attention. Of course, Cabaret has been hugely appreciated by queer audiences for the past five decades – a fact that certainly qualifies the film as a classic.

Julie Vaillancourt: For me, a classic is a work that crosses time, eras, a bit like a good wine that ages well, but which also brings a new artistic proposal, whether in form or subject, as is the case with À tout prendre and Il était une fois dans l’Est. These two films not only subvert and expand the “queer” canon but define it in a certain way, at least in Quebec, by positioning themselves as pioneers. A first-person cinema with an equally personal aesthetic that flirts with direct cinema where Claude admits loving “boys” in whispered voice-over, all the while in a relationship with a black woman (a first on Quebec screens). It’s 1963! Isn’t that subversive? Seeing queers on the big screen in the streets of Montreal stopping traffic on “la Main” (our main North-South artery) in 1974, doesn’t it seem to embrace the Stonewall vibes and reinforce LGBTQ+ visibility in public space?

Do you see your book as drawing attention to undervalued issues, works, or voices within 2SLGBTQ+ movie/artistic culture?

Jon: In a funny sort of way, yes! I write in the book that Joe and Ratso in Midnight Cowboy are like an old married couple. They live together as a couple and they love each other but they don’t appear to have sex. Yet they are still queer for each other, despite the relationship being non-sexual (as opposed to “platonic”). So much of queer culture hinges on the idea of sexual desire and active sexuality, but what about those queer couples where the partners are not sexually active? Few 2SLGBTQ+ works explore that kind of relationship, particularly with regard to older couples who may no longer be sexually active. This is just another way of me saying that Midnight Cowboy challenges some of the usual ways that we define sexual identity in queer works.

Julie: Even if À tout prendre was critically acclaimed, there was a lot of homophobia in the critical reception when it was released in the sixties. As for Il était une fois dans l’Est, the film was undervalued and the critical reception was not that great, even if the film was screened at Cannes. My book draws attention to those issues, and to many more, like the everlasting invisibility of lesbianism in artistic culture (and how lesbians found their own voices and expressed their own concerns in Quebec in the seventies through video), but also to more contemporary voices in queer cinema like Xavier Dolan and Bruce LaBruce, to international classics like La Cage aux Folles, The Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert, and Hedwig and the Angry Inch, and to how Il était une fois dans l’Est and À tout prendre paved the way for these queer film classics.

This blog brings together three authors, two of 2023 books and one of a forthcoming book, who engage with “Stonewall era” films. Why is this period important? Did anything strike you in the others’ books? Baby boomer Waugh remembers the release of these four films. You three authors are relative youngsters who were not even born the year of Stonewall, and Hays was scarcely out of diapers. What attracted you to this period and what surprises, pleasures, and frustrations lay in wait?

Jon: I was born in ’67, right in the middle of the Summer of Love! Midnight Cowboy was shooting at the time of Stonewall and is often attributed to that period as one of its key films. But actually it’s more a product of the postwar, pre–“gay liberation” era, especially in its portrayal of the male hustler. It’s Hollywood’s version of the hustler subject matter that had already occupied gay culture for decades. But Jon Voight’s character is the epitome of the pansexual New York hustler of the 1940s–1960s that novelists like John Rechy (City of Night) were writing about at the time – before sexual identities solidified in the 1960s and 1970s.

Julie: I believe the reason why this period is important is the same reason why it appeals to me. Activism comes out, in the street and on film, to finally raise voices against injustice. Gays, lesbians, drag queens and kings, trans people combine their efforts to walk towards equality together. The cinema is finally freed from the last hints of the Production Code; the impulses of sexual and homosexual freedom are displayed on the screen (I must say that Midnight Cowboy made an impact when I saw it for the first time back in the classroom, and Jon, your book underlines so many interesting points in regards to cultural changes during the Stonewall era and also the X rating). That said, despite all these promises of new freedoms, repression is never far away (e.g., the police raids that will follow in gay and lesbian bars) and I think that’s what frustrates me more. We take two steps forward, but we take one step back. That said, history repeats itself. I’m going to make what may seem like a digression here, but just think about abortion rights being challenged right now! There is an abortion in Il était une fois dans l’Est and it’s evoked in À tout prendre. Have we learned nothing from past struggles ?

Mikhel: The creators of Cabaret were cautious, I gather, about how this type of popular movie would be received within the 1970s context, post-Stonewall and civil rights. The question of how to treat queerness on film was central to many production discussions. For example, director Bob Fosse wanted to dodge what he called “that limp-wristed fag stereotype” in his treatment of the protagonist, and likewise, the screenwriter Jay Presson Allen avoided “any word or gesture that could possibly be defined as faggoty.”

It’s curious to me now, after reading Jon’s fabulous book, to consider differences between a largely hetero film crew avoiding such faggotry in Cabaret, and gay Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy, which, although not always exactly sympathetic to queers, is full of “tutti-fruttis” and so many “faggots.” I also want to mention Julie’s astute reading of Quebec cinema into “Je me souviens,” and how queerness has been used as an elaboration of national identity in French Canada. So, this era saw these different deployments of queerness that manifest in really idiosyncratic and coded, ambiguous representations of sexuality in all of our films.

What was the discovery that surprised you the most in your research?

Jon: This relates to what you were saying, Tom, about the evaporation of the Production Code and the enabling of new freshness for “fag stuff,” and also to the notoriety of Midnight Cowboy receiving an X rating at the time of its release: the fact that the studio – United Artists – opted for an X in order to avoid – in effect – “promoting” homosexuality to young people. Such were the prejudices in ’69. But the studio also worked hard at gaining serious critical attention for the film, for it to become acclaimed as a film of quality with adult themes. So you get a real sense of Midnight Cowboy being a part of the push-and-pull of cultural change during the time of Stonewall. What I found so fascinating about your book, Mikhel, is that, as you say, Cabaret looks at Weimar Germany through a 1970s America lens, mythologizing the era to reflect the concerns of a post-Stonewall North American society. I loved the way you picked that apart and used your art historian’s eye to look at the artifacts from Germany to say, “This is what it was really like.” And Julie, you capture the moment of cultural upheaval during the Quiet Revolution so wonderfully in your account of Québécois cinema at that time.

Mikhel: So many things. Let me pick two. First: how important queer women were to Weimar Berlin art and performance. From painting and advertisement to abortion rights agitprop theatre, lesbians set the standard in the 1920s and ’30s. And second, it was super insightful to follow Cabaret through its successive adaptations of the Isherwood stories. From versions of the stories on stage and screen before the 1972 film to drafts of the screenplay and stage productions over the past fifty years, Cabaret has carried forward a heritage of multiple generations of queer critical insights into gay liberation, civil rights, and white nationalism.

Julie: Mikhel, I just love that you underline the lesbian scene in the republic of Weimar. Few people know about the pioneering work of writer Christa Winsloe and her theatre piece Madchen in Uniform (1930) being the inspiration for the film of the same name directed by Leontine Sagan a year after and generally recognized as the first lesbian film in the history of cinema, although it transcends this label. Germany is a pioneer here and you bring us a fresh view due to the Berlin art and performance scene. I must say that the fact that your reading of Cabaret comes from an art historian’s perspective widens my reading of the film, and I believe that we can all benefit from a multidisciplinary reading of art. This being said, the genesis of my book comes from a film studies perspective. I began my master’s thesis fifteen years ago. At that time, I discovered through my research an exciting world of activism, where a form of mutual aid and solidarity coexist between the gay and lesbian communities of the time in order to work together to advance their respective rights. This is what motivated me to get involved later. Of course, I had seen it in the movies, but to see it in the literature reviews during my research, and later in the field, was an exciting process. The images on the screen, the writings, and the real life influencing and nourishing each other.

What do you most want readers to take away from your book?

Jon: I think the key message of Midnight Cowboy is that you don’t necessarily have to identify as queer in order to have had gay feelings or gay experiences. This keys into the film’s historical context: pre-Stonewall, pre-identity politics (it’s based on a novel by James Leo Herlihy written in 1965). Midnight Cowboy represents an era before the heterosexual-homosexual binary became entrenched, a more fluid sexual landscape than today. I see it as a transitional work in that way. The film doesn’t necessarily reify gay identity but it suggests that many men have known these emotions without being willing to name them.

Julie: First, I hope they would want to watch these two movies or look back at them, if they have seen them a long time ago, just to realize how they were in the avant-garde, in terms of aesthetics and representation of sexual minorities. Also, my book aims at a “Je me souviens” (“I remember,” the motto of Quebec): I hope Quebecers revisit and remember their history and that others discover why our people have a different voice, not only in terms of the spoken language, but also in our way of viewing the world. History shapes our gaze. Ultimately, this has an influence on the way we make films. Finally, I do hope this book reconciles viewers with the artistic vision of Jutra and that it feeds minds in this “cancel culture” era.

Does 2SLGBTQ+ film/culture suffer from amnesia? And culture-centricity? (Why have Julie’s two great classic films from Quebec not broken into the international queer canon?) Other problems with our range of vision?

Julie: It’s not just 2SLGBTQ+ film/culture that suffers from amnesia … What about the average Quebecer and their history? What do they really remember? Ironically, the motto that appears on the registration of all vehicles in Quebec is “I remember.” I devote a whole chapter of my book to history and memory, which we so often lack, unfortunately. Is it because we refuse to see certain flaws in our own history and way of being? The notion of memory of the artwork, and that of Jutra in particular (his damnatio memoriae in connection with the scandal), was for me a way of precisely underlining certain problems of visions which remain. And for your question, Tom: “Why have Julie’s two great classic films from Quebec not broken into the international queer canon?” Maybe part of the answer lies in this question: “Why do so few French-speaking Quebecers barely know your theories on these two Quebec films?” The vision is sometimes narrow in my opinion, and the term culture-centricity seems right. Finally, in a discussion of LGBT film/culture, the question of funding cannot be taken out of the equation, where until recently LGBT artists and films suffered from underfunding. Without money, they have little distribution, and without distribution, the audiences are not there. In this sense, it’s difficult for films with relatively unknown artists at the international level to break the international queer canon.

What is your personal favourite title or guilty pleasure from the queer film canon? Who is your personal favourite 2SLGBTQ+ director or artist?

Jon: I’ve always been partial to Gus Van Sant’s work, not just because My Own Private Idaho is one of the great hustler movies clearly influenced by Midnight Cowboy! I’ve always admired his ability to bend classic narrative and his experimental approach to film form. I think he’s a filmmaker who queers the medium. I even liked his version of Psycho for that reason. I love that he cast Anne Heche in the Janet Leigh role! Elephant was another great film that messed with the medium. Also, I love Bruce LaBruce’s Hustler White because it’s so much fun and so irreverent.

Julie: I must say, Jon, I like your expression of “queer(ing) the medium.” And I think this adds to the difficulty of the question in itself … How can we choose just one film? Besides Il était une fois dans l’Est (it’s not only a question of queer representation for me, but also an honest and rare depiction of the French Canadian becoming a Québécois, with its own language and identity in the period of the Quiet Revolution), I must definitely say Anne Trister from Léa Pool, one of my favourite directors. In fact, I would have gladly written on this film for the QFC series but had already published a substantial reflection on it in Cinematic Queerness (2011). Same with C.R.A.Z.Y. by Jean-Marc Vallée, but Robert Schwartzwald had already done that superbly for the QFC series. Getting outside of Quebec and in a more contemporary era, I must say that one of my guilty pleasures is La vie d’Adèle (Blue Is the Warmest Colour) by Abdellatif Kechiche. I know this may come as a surprising choice, regarding the scandal at Cannes (the way Kechiche treated his actresses, and the overtly “pornographic” sex scene, the only scene hetero men remember probably) … This being said, I remember at the end of the press screening, the lights went on and I was still crying like a baby … The talent of the actresses, the authenticity of their relationship moved me deeply. Being honest, I had not recognized myself in a movie for a long time, but this one spoke to me. And for those rare times, I stopped “analyzing” the film and actually watched it, FELT it. I think this is a challenge sometimes for film critics and theorists … Don’t you think, Mikhel and Jon? I know this film has the imprint of the graphic novel by Jul Maroh, from which the film is adapted, and even if the author felt the film did not pay homage to their work, regarding the female gaze, it was a guilty pleasure film to watch, for me. On the funny side, Le Placard (The Closet, 2001) by Francis Veber remains for me a true queer film classic that has aged surprisingly well in terms of being politically (in)correct in an era defined by the multiple politics of sexual identity.

Jon: I completely agree, Julie. Midnight Cowboy has always had a personal effect on me. I found writing some parts of the book very painful.

Mikhel: My guilty queer film pleasure? Cabaret! Of course! The guilty appeal of musical films in general is felt especially by marginalized adolescent queers obsessed with art, theatre, and music. (Yes, Julie, FELT!) Musicals are the zenith of hammy sentimentality and sappy, camp, effeminate expressivity – not to mention diva worship of degraded celebrities like Liza, who are important for many people’s queer identity formation. Musicals are corny and cringey and occupy a register of bad taste and “low” cultural forms that appeal to special types of homos like myself.

Other than that, I’ll thirstily drink in anything by Almodóvar. I’ll always adore John Waters. And I love many queer visual artists who make moving imagery. Two people who excite me right now are Wu Tsang and Michèle Pearson Clarke.

The international queer film festival industry is plugged into the voracious cinephilia of sexual and gender minority communities around the globe. Anything we are doing right? Anything wrong?

Jon: I’ve always felt that there was a danger of queer cinema becoming ghettoized just by virtue of specialist distributors marketing queer films to a narrowed-down target audience. I’m thinking of UK companies like Peccadillo Pictures who crossed over into world cinema as a way to broaden their own remit and hopefully the potential audience for their own titles as well. They mix up “gay interest” with arthouse to avoid the stricter confines of distribution. It’s always great when a movie like Portrait of a Lady on Fire comes along and finds its way into more mainstream distribution – but I suspect that’s because it’s marketed primarily as arthouse. It’s always a bit depressing to go onto Netflix or other streaming platforms and see movies labelled as “gay interest,” like it’s a discrete genre, and confined to that category, even if, admittedly, more and more titles are getting distribution thanks to streaming.

Julie: I cannot agree more, Jon. I think it’s great to see more images of ourselves on the big screen and that all the diversity of the LGBTQIA2S+ acronym is more and more represented. That said, I find that women’s cinema, for example that made by women about lesbianism, is not yet sufficiently visible compared to other realities and that it is often confined to more underground festivals with fewer means of distribution. Nevertheless, this is bound to change (yes, thanks to Sciamma’s enduring work), and it will change even more as women find themselves behind the camera to express their realities, but also at the head of festival programming. In this sense, I can only salute a festival like image+nation, in Montreal, but also all those festivals that hang on internationally at a time when LGBTQIA2S+ realities are increasingly displayed on television and streaming platforms. I wonder what impact, whether positive or negative, this will have on the international queer film festival industry …

Jon, you’re a film critic and a horror film specialist. Julie, you’re a teacher and film critic/“lesbian columnist” for a gay magazine. Mikhel, you’re an art historian. How do your respective starting points shape your engagement with your films and your readership?

Jon: I was attracted to the potentially subversive aspects of horror cinema, and its diverse voices, especially in recent times. The genre doesn’t celebrate “difference” exactly but does glory in it. Queer horror is definitely a thing. The genre has always had its queer icons, like Ernest Thesiger in Bride of Frankenstein! I’ve always thought the horror genre could represent some form of alternative/oppositional cinema and appeal to those who identify outside of the heteronormative mainstream, or even those who, culturally and politically, just see things a little differently. The theme of the outsider is key to the horror film, and is also a crucial aspect of Midnight Cowboy.

Mikhel: Cabaret is full of references to German art of the 1920s and ’30s. Its opening scenes are full of tableaux that reference the “Neue Sachlichkeit” paintings of Otto Dix, George Grosz, and Jeanne Mammen. So, my reading of the film contextualizes mid-century American liberation struggles within this history of Weimar Berlin in an effort toward tracing a legacy of politically engaged art.

Julie: Ironically, I must admit that my starting point was in fact the viewing and analysis of these two films twenty years ago (probably in one of your classes, Tom!). They changed the way I looked at the movies: I finally saw my communities on the big screen as I had never seen them before. These films shaped my next engagements in the Montreal LGBTQ community, starting with Fugues magazine. A few years ago, I started showing À tout prendre and Il était une fois dans l’Est in my film classes. The way the younger generation responds to these films gives me faith in them – the students, but also the films and their quality as queer film classics. It also gives me faith that yesterday’s activism makes today’s society freer. Although there is still (a lot of) work to be done (particularly for women’s rights) … In short, I tried with this book to close the loop on my reflection of a few decades on these two films, but also on their places within Quebec and international cinema, especially with the place of art in society. Because in the end, my starting point has always been this enormous passion and respect for arts and creation and whether in the classroom or on paper, I will never stop teaching, speaking, or writing about it.

Matthew Hays is a Montreal-based award-winning author and journalist, with publications in The Guardian, The New York Times, Cineaste and The Walrus. He is the film instructor at Marianopolis College and a part-time faculty member at Concordia University, where he teaches courses in media studies.

Thomas Waugh is Distinguished Professor Emeritus in Film Studies and Sexuality, Concordia University, Montreal. Among his many books are Hard to Imagine: Gay Male Eroticism in Photography and Film from Their Beginnings to Stonewall, The Romance of Transgression in Canada: Queering Sexualities, Nations, Cinemas, and The Conscience of Cinema: The Works of Joris Ivens 1912-1989.

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.