Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

This post was previously published on October 7, 2020.

For the first time in the long history of the Olympics, the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games have been postponed until summer 2021 due to COVID-19. Unfortunately, this was not the only sporting event affected by this year’s pandemic—various leagues, tournaments, and competitions had to adapt to this new reality. The International Olympic Committee, however, has recently shared their optimism regarding the creation of Olympic Games fit for a Post-Covid world.

While we patiently await their return, MQUP author Jonathan Finn offers us a throwback to Olympic Games and sporting events of the past through his exploration of the history of the photo-finish in sports—a technology often relied on during Olympic Games. His exploration of the cultural and technological impacts of this seemingly objective technology brings into question the ways in which we understand human physical performance and ability, as well as the ways in which we engage with sports.

Jonathan Finn’s new book Beyond the Finish Line: Images, Evidence, and the History of the Photo-Finish shows how innovation was animated by a drive for ever more precise tools and a quest for perfect measurement. As he traces the technological developments inspired by this crusade—from the evolution of the still camera to movie cameras, ultimately leading to complex contemporary photo-finish systems—Finn uncovers the social implications of adopting and contesting the photograph as evidence in sport.

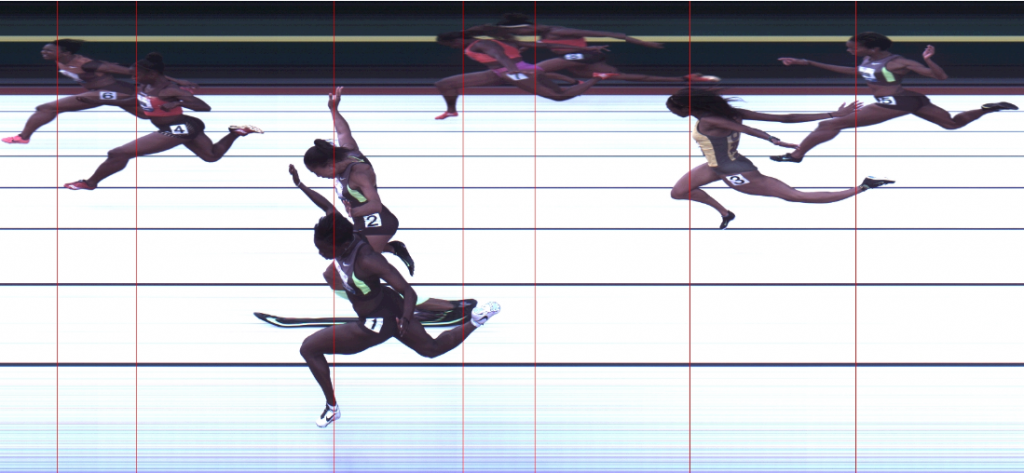

During the 2012 US Olympic Trials two runners in the women’s 100M race, Jeneba Tarmoh and Allyson Felix, tied for third place in a photo-finish of 11.068 seconds. As both a track fan and a scholar of photography I knew that track and field and other sports employed highly precise timing and imaging equipment. I wondered why such cameras capturing data to the thousandth of a second couldn’t separate the two competitors? Surely, there was a single image that showed Tarmoh ahead of Felix or vice versa. And so began a project to research and write a history of the photo-finish.

Inside camera photo-finish of women’s 100m, 2012 US Olympic Trials. Photo courtesy and copyright of Lynx System Developers Inc.

The true photo-finish camera, called a slit camera, was developed in the 1940s. However, beginning in the 1880s, photographers and sports enthusiasts claimed that the photographic image had ‘solved’ the dead-heat in sport. The logic was simple enough: a photograph would be able to reveal differences the human judge could not see. As camera technology became more precise, so too did the measurement of sport performance. In the early Olympic Games of the 20th century, timing was typically done to the 5th of a second. This changed to tenths relatively quickly and to hundredths and thousandths over the ensuing decades. Current photo-finish systems capture data to the 10,000th of a second with the world-leader OMEGA boasting its ability to subdivide the second into millionths.

“Winning the high jump” image published in Outing magazine, vol. 13 (1888–89), 112.

One curious reality of the photo-finish is that, dividing the second into millionths, billionths, or beyond still would not eradicate the dead-heat. This is due to a simple but largely unacknowledged truth: precision does not equal accuracy. Not long after the mid-20th century we reached a point where the technological precision afforded by the camera outpaced what could be guaranteed in the live environment. Sports take place in the natural world where venues are made of dirt, grass, rubber, water, ice, snow, sand, concrete, and other materials. Even in tightly controlled environments such as a pool, there can never be a perfectly equal playing-field. This is recognized in the rules of the Federations that govern individual sport such as World Athletics, the Fédération Internationale de Natation, and the Fédération International de Ski. These Federations allow for dimensional tolerances in the physical configuration of event venues. As regards swimming pools, any individual measurement between two endpoints can vary by 3mm. This difference may seem miniscule and unimportant, but timing to a thousandth of a second or beyond actually records distances covered by the athlete that is less than the allowable differences in the pool’s construction. In other words, race results differentiated at the thousandth of a second or beyond can actually be due to miniscule differences between the lengths of pool lanes rather than athlete performance. As one former photo-finish expert put it to me: the difference at that level of timing could be due to differences in the thickness of paint on the pool walls rather than to athletic performance.

“1500 M. Flat, Final. The Finish.” From the Official Report of the Olympic Games of Stockholm 1912, plate 131.

Such was the case in the Tarmoh / Felix dead-heat. Cameras recording at 5000 and 10,000 scans per second could not separate the two athletes. Why? Because in the effort of competition Tarmoh’s torso was rotated and obscured from view in the photo-finish images. Placing in track is determined by the forward most point of the torso and photo-finish judges could not say with certainty that one athlete’s torso crossed the line ahead of the other. Timing to the millionth would have made no difference. Greater precision did not and does not mean greater accuracy.

Why then do we continue to employ equipment that is ever more precise and promote technologies like the photo-finish, instant-replay, and video review as eradicating human error? Because sport is about deeply held and often cherished beliefs. The quest for ever-more precise technology is about preserving the pursuit of ‘faster, higher, stronger’ that is endemic to sport. It’s about preserving our belief in technology to solve perceived human problems. It’s about preserving the myth that mechanical devices like cameras produce objective evidence. And it’s about preserving the existing social order (in sport and beyond) which pits individuals, nations and corporations against one another in a win-at-all-costs culture, with all the financial and cultural capital that flows from victory. In this way, the photo-finish is a fascinating object both for what it makes visible and for what its history reveals.

Photo-finish of the men’s 100m at the 1972 Munich Games. From the Official Report of the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich, 159.

Jonathan Finn is associate professor of communication studies at Wilfrid Laurier University. More information on Beyond the Finish Line: Images, Evidence, and the History of the Photo-Finish >

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.