Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

“While diseases may differ one from another, these essays also show that human reactions to new diseases are relentlessly constant.” Jacalyn Duffin, SARS in Context

For many, when considering the current COVID-19 pandemic, the SARS outbreak that swept across the globe in 2003 comes to mind. While there are significant differences between the two, the similarities are undeniable. Both respiratory illnesses are caused by coronaviruses, are highly contagious, and have had a significant and destructive impact on healthcare services and our communities, to name a few. Taking these similarities into consideration raises the question, what can we learn about COVID-19 and our current response to it from our past dealings with the SARS outbreak?

In light of this ongoing health crisis, McGill-Queens University Press has made available a complete and free version of the book SARS in Context: Memory, History, and Policy edited by Jacalyn Duffin and Arthur Sweetman. Based on a symposium held at Queens University in 2004, one year after the outbreak, SARS in Context provides analysis from physicians involved in the crisis, historians, and policy experts, reflecting on the virus’s scientific, historical, economic, and political impact.

This week’s guest blogger, physician and historian Jacalyn Duffin, explores the parallels between both crises and helps us understand how her book relates to COVID-19 and our current dilemma, shedding light on how, and what, we can learn from our past.

As COVID-19 rages, parallels are sought with the coronavirus epidemic of 2003, and we have had numerous requests for access to our 2006 edited volume, SARS in Context: Memory, History, Policy. With libraries closed and the hardcover price at more than 100 dollars, we were delighted when McGill-Queen’s University Press agreed to make this book freely available online. Revisiting it brings back memories of its origin in a wonderful and unusual symposium held at Queen’s University on 10-11 February 2004. The gathering brought together front-line physicians, historians, policy experts, and economists to reflect upon SARS.

The contributors are once again being invited to explain COVID-19 and predict the future. It is humbling to admit that our responses differ little from those that we gave during and following SARS. Historian Charles E. Rosenberg claimed that responses to epidemics follow stages, reminiscent of Kubler-Ross’s stages of grief: denial and panic, commitment to one or more explanatory framework, negotiating public responses, and ending with restoration of “normal” life and some new knowledge.

Historians attending the SARS symposium at Queen’s University, February 2004. From left to right Russell C. Maulitz, Jay Cassel, Margaret Humphreys, Georgina Feldberg, Paul Potter, Jacalyn Duffin, Heather Macdougall, Ann Carmichael, Naomi Rogers, Codell Carter.

The SARS outbreak was sharp with steep mortality, especially of health-care workers, but it was mercifully short and quickly contained by the ancient methods of hygiene, screening, isolation, and quarantine. Then it vanished. SARS affected mostly China and Canada, where it left structural changes on public-health organization; however, its impact on the rest of the world was minimal. Despite our book’s riveting first-hand accounts, its historical references to plague, cholera, polio, tuberculosis, influenza, and sexually transmitted diseases, and its economic analyses with practical recommendations for policy change, our book was never a bestseller. SARS was quickly forgotten everywhere else.

The disease most often invoked in comparison to COVID-19 is the 1918 influenza pandemic, the so-called “Spanish” flu. During its centennial in 2018, the world seemed complacent, and I discovered that journalists often sought a triumphalist narrative and had trouble accepting that humans will always remain vulnerable to new diseases. Similarities shared by 1918 flu and COVID-19 include symptoms, global spread, and post-germ-theory context. Furthermore, many unknowns and apparent impossibilities tracked influenza, just as they do COVID-19:

• how many are asymptomatic carriers?

• what is the incubation period?

• does recovery convey immunity?

• will any treatment ever prove effective?

• can passive transfer of antibody afford a method of control?

• is a vaccine likely?

Nevertheless, there are significant differences. Unlike 1918 influenza’s predilection for young adults, COVID-19 is more deadly for the elderly and possibly the very young. The advent of antibiotics and ventilators means that affected people have a better chance of surviving the ravages of coronavirus provided they have access to health care.

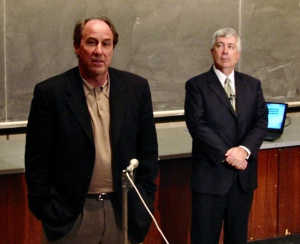

Dr David M.C. Walker, Dean of Queen’s School of medicine introduces Ontario Coroner Dr. James Young. Dr Walker chaired the Expert Panel on SARS and Infection Control, 2004.

The social context of the two pandemics also differs in ways that COVID-19 shares with SARS. Influenza simmered for a long time before Spain announced its problem. Three decades later, the World Health Organization (WHO) was established to monitor disease and share information to help manage emergencies internationally. WHO’s efforts to alert, track and advise have made great improvements, but when sacrifice is needed, opposition arises, as it did during SARS and is doing now on a grander scale.

Another difference between COVID-19 and 1918 influenza is that most democratic nations now have social-welfare systems that attempt to address the economic harm to those who are ill and/or obliged to comply with public-health rules for isolation and closures. These governments accept a need for public investment to sustain their citizens and stimulate recovery in the aftermath. Each nation does it differently, but mid-crisis supports for the unemployed during disease are occurring on an unprecedented scale. As Sweetman indicates, the costs are enormous, the choices are difficult, and the controls impose obligations on everyone to protect the few; yet, James and Sargeant reveal that economic recovery in both 1918 and following SARS was quicker and more robust than had been feared.

As Macdougall and Feldberg both explain, each disease leaves a public-health legacy in terms of structures and policies to rectify the perceived inadequacies of measures created in the aftermath of earlier epidemics. SARS was no exception. In Canada, several reports prompted greater investment, the 2004 creation of the Public Health Agency of Canada, and numerous energetic endeavours for pandemic planning at institutional, municipal, provincial, and national levels. It remains to be seen if these changes will have given Canada any advantage over other nations in confronting COVID-19, especially in contrast to its nearest neighbor. But nature is endlessly inventive. Each new disease brings novel parameters that will inevitably challenge the safeguards spawned by managing scourges past.

Carter reminds us of the epistemic tyranny of causal disease concepts anchored in the notion of a single pathogen — and the attendant expectations of vaccines to prevent or drugs to cure. SARS was immediately received into that framework and the pathogen identified. So too with COVID-19. No doubt, the new coronavirus is a necessary cause of this disease — but it needs “more” to be sufficient for spread. That “more” can be disrupted by social distancing, isolation, quarantine, ramped-up hygiene — and yes by a vaccine should one ever become available.

In taking a long look at the “causes” of new diseases, physician-historian Mirko Grmek argued that the pathocenosis (prevalent diseases specific to time and place) may be affected by human actions, including the best-intentioned medical advances: antibiotics have given rise to resistant organisms; vaccine-based elimination of major pathogens creates windows of opportunity for novel entities. Pollution and climate change are said to favour the emergence of killer bees. Some have even suggested that this new coronavirus is a symptom of “Gaia sickness.”

In the aftermath of COVID-19, we can anticipate new public-health strategies and clever technological inventions, but we should also expect changes in society itself–working and schooling from home, fewer in-person meetings and conferences, less air travel, greater transparency and understanding about national and international drug security. A by-product of these changes to our way of life may be a healthier globe. Did Gaia create the coronavirus to heal herself of the harm we have done to her?

Jacalyn Duffin, physician and historian, is professor emerita at Queen’s University, where she held the Hannah Chair in the History of Medicine from 1988 to 2017. She is the author or several books, including Stanley’s Dream: The Medical Expedition to Easter Island and co-editor of SARS in Context: Memory, History, and Policy.

For more information on SARS in Context: Memory, History, and Policy >

For a free PDF version of SARS in Context: Memory, History, and Policy >

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.