Canadian Store (CAD)

You are currently shopping in our Canadian store. For orders outside of Canada, please switch to our international store. International and US orders are billed in US dollars.

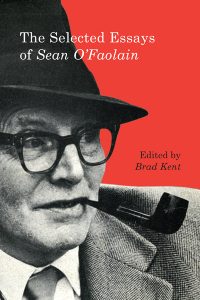

Brad Kent’s new book The Selected Essays of Sean O’Faolain, was recently reviewed by Fintan O’Toole for The Irish Times.

The following is an excerpt from Fintan O’Toole’s piece. The full review is available on the The Irish Times website.

For Fintan O’Toole, these ‘hard and enduring’ polemics are a testament to O’Faolain’s courage as a critical thinker in narrow-minded Ireland

In the blurb on my US edition of Sean O’Faolain’s last novel, And Again? (1979), he is described as “the greatest of Ireland’s living novelists”. Hyperbole comes with the territory, of course. Even so, this claim now seems beyond the bounds of ordinary exaggeration.

In the blurb on my US edition of Sean O’Faolain’s last novel, And Again? (1979), he is described as “the greatest of Ireland’s living novelists”. Hyperbole comes with the territory, of course. Even so, this claim now seems beyond the bounds of ordinary exaggeration.

So far as I know, no new editions of O’Faolain’s novels or short stories have appeared since the 1980s. The work of the contemporary with whom he is so often bracketed, Frank O’Connor, is easily available, including, for example, in the prestigious Everyman series. But O’Faolain’s fame as a creative artist has waned to a point of near-invisibility.

It is not a fate he deserves, but, in respect, he has only himself to blame: O’Faolain the artist is now overshadowed by O’Faolain the public intellectual. His epic courage, skill and sheer endurance in holding open a space for critical thinking in the decades when the Irish State was at its most narrow-minded and inward looking seem more important than what his alter ego in And Again? calls the “plenitude of tiny depth-giving brush strokes” that are the business of the writer of realist fiction.

Brad Kent’s superb selection of 55 essays (about a third of O’Faolain’s total output) is likely to deepen the shadow cast by his witty, learned, vigorous and wonderfully engaged journalism over his more imaginative output of stories and novels.

In the last essay collected here, a self-portrait from 1976, O’Faolain complains that “I had to spend half my working life beating the pavement between one lamp-post and another like a tart, trying to earn enough money to support my beautiful goldenhaired mistress, my beloved duck and darling, my exigent Muse”. His Muse may not have thanked him for his efforts: it is striking that he did not produce a single novel between 1940 and 1979, and the energy he put into his polemical journalism is surely a major factor in this long hiatus.

However, posterity will surely feel grateful. The essays – for The Bell (of which he became the founding editor in 1940), for TS Eliot’s Criterion, Cyril Connolly’s Horizon, HL Mencken’s The American Mercury and many of the other leading journals of the mid-century Anglosphere – were certainly written with an eye to making a living. But if they are a form of prostitution, O’Faolain is a very high-class escort.

As an Irish polemicist, O’Faolain’s passions are essentially parricidal. He had some experience in figurative father-killing, having rebelled against the whole world of his loyalist father, a Catholic member of the Royal Irish Constabulary, to become an ardent nationalist. In that self-portrait, he describes the Easter Rising as “the greatest trauma of my life”. But he went on to kill at least two more fathers: his great mentor in Cork, the critic and writer Daniel Corkery; and his own one-time political hero, Éamon de Valera.

One of the centrepieces of the book is O’Faolain’s long demolition of Corkery, which appeared in The Dublin Magazine in 1936. He writes of how, as young man, he was enamoured of Corkery’s stories of the Irish revolution – until, that is, he joined it himself: “The more we saw of revolution, the less we liked Corkery’s lyric, romantic idea of revolution and revolutionaries.”

This is very gentle indeed compared with his assaults on Corkery’s Synge and Anglo-Irish Literature (1931), which he compares to Nazi thought, and on The Hidden Ireland (1924), from which he plucks examples of prize eejitry and sprinkles them with drops of acid. A line is being drawn between O’Faolain and all the absurdities of official cultural nationalism, of which Corkery was the chief propagandist.

This is only a warm-up for his assault on de Valera. The grudge is again personal: just as Corkery had been an intellectual exemplar for his young self, Dev was the Chief whom he followed into the Civil War, in which O’Faolain served as a Republican bomb-maker and propagandist. In his 1945 attack on his lost leader, he admits to having once admired de Valera “this side of idolatry” – without mentioning that he had, in fact, written a hagiographic book about his hero. Read more >

Read the full review on the Irish Times website.

Learn more about The Selected Essays of Sean O’Faolain.

back to all news

back to all news

No comments yet.